[2. History of the VSC and the protests of 1968] [Return to Intro] [4. Infiltration by the Special Demonstration Squad]

Table of Contents

Introduction and background

The first few sections of this article looked at the organisations behind the protests against the Vietnam War in 1968. In this and the following sections, the emphasis will be on what can be learned from Metropolitan Police Special Branch material related to that period collated at this site. It will also incorporate new material as it is released by the Undercover Policing Inquiry.

In order to understand how undercover officers from Special Branch’s undercover unit, the Special Demonstration Squad, were able to target the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign we need a closer view of how the campaign was organised on the ground.[1]For an overview of the Special Demonstration Squad, see: Special Demonstration Squad, Powerbase.info, 2013 (accessed, 10 March 2018). For this reason we start with setting out what is known of local branch structure of the VSC in London. This will allow the material from the Inquiry to be put in context.

One role of Special Branch is monitoring of political groups, which at the time was known as counter-subversion. Later, those considered subversive were relabeled as ‘domestic extremists’,[2]For an overview of Domestic Extremism as a concept, see: Peter Salmon, Domestic Extremism, Powerbase.info, 2015 (accessed, 10 March 2018). and the modern incarnation of counter-subversion is to be found in the PREVENT programme.

In the late 1960s, Special Branch worked in conjunction with MI5 compiling and sharing files on political groups and protests of all stripes. For this, both agencies had dedicated ‘desks’ or ‘squads’ for collating and disseminating the intelligence gathered. Within the Metropolitan Police Special Branch this was referred to as ‘C Desk’ or ‘C Squad’.

Given current understanding, it appears that until 1968 MI5 ran agents and informers inside groups, while Special Branch focused on collecting information from various sources – including what is now referred to as ‘open source intelligence’. Special Branch also engaged in surveillance and regularly recruited informers (or turned activists into such). Prior to September 1968, and the founding of the Special Operations Squad (as the Special Demonstration Squad was then named), it appears that Special Branch did not deploy police officers undercover into groups in a sustained fashion, though it would have sent plain clothes officers along to meetings, etc. However, as police officers, Special Branch, and not MI5, had the power to carry out arrests and other legal powers. Another aspect of Special Branch activity was to feed into mainstream policing by providing intelligence around public order issues such as demonstrations, indicating what uniformed officers could expect on the ground; it focused less on actively running criminal investigations, though it would provide support to them.[3]Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, BiteBack Publications, 2015.[4]Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5, Penguin, 2009.[5]Rupert Allason, Branch: A History of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch 1883-1983, Secker & Warburg, 1983[6]Robert Fleming & Hugh Miller, Scotland Yard: The True Life Story of the Metropolitan Police, Signet Books, 1994.

Though there is as yet no public documentation showing the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and its associated political groups were under direct surveillance by ‘C Squad’, it is highly unlikely that they were not being monitored. According to his obituary, Detective Inspector Conrad Dixon had responsibility for monitoring Trotskyists and anarchists on behalf of Special Branch in 1968.[7]Conrad Dixon (obituary), The Times, 28 April 1994 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK). A Special Branch report on the Youth CND demonstration of 24 March 1968 (see part 1), shows that the unit’s officers were present actively spotting communist, anarchist and Trotskyist activists in the crowd, indicating they knew the faces of those they were monitoring.[8]Special Branch report in relation to Youth Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Metropolitan Police, 24 March 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk)

Given the international links the groups organising the demonstrations had with communist governments and revolutionary forces, this would have also made them of interest to the state apparatus of the day.

The protest of October 1967 and March 1968 saw concerted attempts to occupy the US Embassy in Grosvenor Square over that country’s military involvement in the Vietnam War. This politically embarrassed Harold Wilson’s Labour Government at the time. The dramatic rise in student militancy as revolutionary left wing groups gained a burst of life from the May 1968 cultural upheaval, and a fear that the disturbances rocking France would happen in Britain, also focused considerable media attention on the protests.

Thus, following the March 1968 anti-Vietnam War protest, all attention turned to the demonstration planned for October that year. The mainstream media ran multiple stories scaremongering violence and threats of bombs. As has happened before and since, a feedback mechanism where police and government fed the media, while press coverage fed political pressure on the police, bringing the promise of further resources. There was a particular fear that the events of March would play out again in October – in larger numbers. So, while Special Branch monitoring would have continued, the significance of such surveillance in establishment circles had dramatically increased.

It is in this atmosphere that Conrad Dixon put forward in September 1968 his proposal to create a ‘Special Operations Squad’, twelve men and women, who would go undercover to learn in more detail what the protestors were planning for the October protest. It was their relative success, in police terms, which allowed the unit to not just continue but also expand. Indeed, many of the SDS infiltrations of the 1970s would target groups either active in, or had roots in, the 1968 protests against the Vietnam War. However, for the purposes of this article, we focus on the period 1968-1969.

Contemporary Special Branch files

Metropolitan Police Special Branch (MPSB) material released through FOIA requests and now archived at SpecialBranchFiles.uk gives some insight into the monitoring of both the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) and associated groups. Many of the reports on the VSC are authored by Conrad Dixon himself and indicate a substantive knowledge of the internal politics of the coalition organising the October 68 protest. However, some of this material has been challenged by prominent VSC activist Ernest Tate,[9]Ernest Tate, On the Secret Internal Police Reports about the 1968 mobilizations against the Vietnam war in in London, England (Letter from Ernest Tate to Solomon Hughes of 27 May 2008, Marxsite.com (accessed 22 August 2017). amongst others.

Monitoring of the VSC in Summer 1968

On 14 August 1968, the then Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, John Waldron, asked regional Special Branches for intelligence they had on the October 1968 demonstration (the actual letter was authored by Peter Brodie, then Assistant Commissioner for Crime, including overseeing Special Branch):[10]Peter E Brodie, Letter to regional police forces requesting information on extremists planning to attend the anti-Vietnam War protest of October 1968, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 14 August 1968, (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

A report by Conrad Dixon of 21 August provides detailed knowledge of the internal workings of the VSC:[11]Conrad Dixon, Special Branch report on Vietnam Solidarity Campaign’s “Autumn Offensive”, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 21 August 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

| This report summarises the progress made to date by the organisers of the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign’s “Autumn Offensive”.

This activity will take place during the week commencing on the 20th October 1968, and the climax will be reached at a large demonstration on Saturday, 26th October. Trafalgar Square is expected to be the initial venue of this demonstration; the booking is yet to be confirmed. The Vietnam Solidarity Campaign acts as an “umbrella” organisation embracing left-wingers of various groups, and these factions are sharply divided as to the employment of violence for political ends. The pro-Chinese Mao-ist adherents are active at present and attending every meeting in London to attempt to persuade all participants to accept the inevitability of violence on a large scale. They are opposed by the International Socialism Group of Trotskyists and the Communist Party who are seeking a demonstration on orthodox lines, and wish to co-operate with Police. The International Marxist Group of Trotskyists is tending to side with the Mao-ists. |

While his report of 30 August notes:[12]Conrad Dixon, Report on Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 30 August 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK).

| A slight change of emphasis has taken place [since 21 August]. The International Marxist Group is retreating from its former support of the Mao-ist line condoning violence and is tending to side with the International Socialist group which favours a disciplined demonstration. The Mao-ists continue to intrigue among the various groups, but are making less progress as news of their machinations becomes more widely disseminated.

Particulars of most of the current members of the V.S.C. Liaison Committee responsible for coordinating activity have been obtained: three belong to the International Marxist Group and four to the International Socialism faction. There is one representative for the Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation, one for the Socialist Medical Association and four for the Communist Party. |

and goes on to say:

| The rank-and-file in [local London] branches are extremely militant: the attitude of the secretaries of the branches is to “wait and see” what the directives of the National Committee will bring forth after the 7th September. |

He also refers to detailed matters within the Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation (R.S.S.F.):

| The [Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation] is aligned with the Mao-ists on the question of violence, and their current thinking is that the demonstration of [27]th of October shall include a march past the offices of Dow Chemicals in Wigmore Street, down Park Lane and through Whitehall. This group advocate their marchers shall be 30-40 abreast, be under strict control, and avoid arrest by linking arms in long rows.

An R.S.S.F. document that has come to shows that this group regards the throwing of missiles at buildings as “permissible” and contains the phrase …”only if the police attempt to break up the march should their lines be attacked”. ”This organisation has 278 members” [emphasis added]: no doubt more will be recruited when the universities re-assemble. |

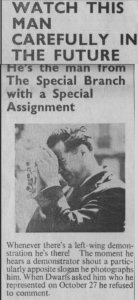

Police raid on the Black Dwarf office

A police raid of 3 September on the Carlisle Street offices of Black Dwarf, triggered a particular round of media attention that shed some light on police activity. During the raid, police found a drawing on a wall of a Molotov cocktail with instructions for making them written along side it. The Guardian at the time gave accounts of the raid:[13]Tariq Ali explains the writing on the wall, The Guardian, 4 September 1968 (accessed 10 February 2018).

| Special Branch officers searched the offices of The Black Dwarf – the “revolutionary Socialist newspaper” – in London yesterday and photographed a diagram on a wall. Scotland Yard said a report was being sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

Mr Tariq Ali, editor of The Black Dwarf, said somebody had “scrawled a rather stupid diagram on a wall two or three weeks ago, showing how to make a Molotov cocktail. I don’t know who did it, it could have been anybody. There are all sorts of people in and out of our offices.” He added: “Of course, the moment I saw it I gave instructions that it was to be erased immediately but, due to the laziness of the staff here, it wasn’t. Actually, they just put two posters over it – they were going to paint it over later.” He said the police must have known about the diagram, which they photographed, as they soon found it although it was covered by posters. Barely readable writing in blue crayon underneath the diagram said the weapon was for use against cars, RSGs (regional seats of government), armoured cars, and buildings, but it was not to be used against individuals, even Fascists. Five Special Branch officers were waiting outside the offices in Carlisle Street when Mr Ali arrived. He said they were led by Chief Inspector Elwyn Johns, who produced a search warrant. They spent about an hour there looking through files and taking measurements of the offices. Scotland Yard said the search warrant had been issued on Friday under Section 55 of the Malicious Damage Act of 1861. |

In 1987 he gave another account, also to The Guardian, where he explained the raid took place the day after a group of ‘hippy anarchists’ slept in the office and did the drawing:[14]Tariq Ali, Street-fighting memories, The Guardian, 1987.

| The very next day our offices were raided by a Scotland Yard. A team of special Branch men and a woman went straight to the poster, removed it and photographed the crudely drawn diagram. A chief inspector interviewed me at length and warned me he would be preparing a report for the director of public prosecutions. He then ordered a search of the offices. |

At the time, the story was picked up by the Evening Standard on 4 September, which expanded on it to report that Molotov cocktails and bombs were being manufactured and stored at secret addresses, while other extremists were purchasing small arms to use against the police. This was also then reported by The Times. A Special Branch report by Conrad Dixon concluded the press were inflaming the situation, the reports being triggered by the Black Dwarf raid, but also writes:[15]Letter of Commander John Smith to the Home Office 5 September 1968 including a report from Conrad Dixon relating to various press reports on preparations for the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign Autumn Demonstration due to be held on 27th October, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 5 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK).

| With regard to firearms, there has been an allegation that a member of the Highgate Vietnam Solidarity Campaign has acquired four revolvers which might possibly be used in the demonstration, but no confirmation has been received to date. Indeed, certain action taken by [Special] Branch has confirmed they are certainly not at the address of this individual. |

The report leaves open several questions: how had Special Branch gained sufficient intelligence to pinpoint an individual, and what was the ‘certain action’ taken?

It is unknown how the media learned of these details, which may or may not have been deliberate. Such reports in prominent newspapers would in turn have produced pressure on the police. And as such, laid some of the political groundwork for the acceptance of Dixon’s proposal to form the Special Demonstration Squad, even though his own report down plays the threat.[16]The report authored by Dixon is quite possibly drawn up in response to a Home Office request for a briefing on lurid stories then circulating in the media regarding the plans for the October demonstration.

Worth noting is that years later Tariq Ali wrote the Black Dwarf offices had been burgled a number of times in 1968 without anything being taken.[17]Tariq Ali, Street-fighting memories, The Guardian, 1987. Such burglaries were conducted by Special Branch to facilitate the bugging of premises to gather intelligence; something that could have helped identify the Molotov cocktail graffiti.

The raid on the Black Dwarf office fed into other sensational press reports, something the police could have expected given the atmosphere at the time.

Thus, The Times on 5 September wrote:[18]Tariq Ali, Street-fighting memories, The Guardian, 1987.

| A small army of militant extremists plan to seize control of certain highly sensitive installations and buildings in central London next month, while 6,000 Metropolitan policemen are busy controlling an estimated crowd of 100,000 anti-Vietnam war demonstrators… This startling plot has been uncovered by a special squad of detectives formed to track down the extremists” [emphasis added] who are understood to be manufacturing “molotov cocktail” bombs and amassing a small arsenal of weapons. They plan to use these against police and property in an attempt to dislocate communications and law and order. |

The following day, the 6 September 1968, The Times, also reported:[19]Clive Borrell & Brian Cashinella, Callahan faces plot questions, The Times, 6 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

| Mr Callaghan, Home Secretary, is expected to be asked for a statement about plans, which have been passed to police, that groups of militant extremists intend to occupy certain central London buildings on October 27.

Several M.P.s, concerned at threatened armed violence [following the previous day’s reports], intend to press for a quick reply when the House of Commons reassembles on October 14. The groups plan to seize key buildings and installations while police are busy controlling an expected 100,000 peaceful demonstrators on an anti-Vietnam war march. Scotland Yard yesterday issued the following statement…. “Some of the press comment is factual, but some is speculative and likely to arouse public apprehension unnecessarily. The police know of no reason at this state to assume that these demonstrations will involve forms of violence appreciably different from those experienced in London earlier this year”. |

The Times went on to state:

| However, at least 20 members of the militants’ executive committee will meet this weekend at a secret address in a north Midlands city. It is at this meeting that final plans are expected to be laid. |

This is highly likely to a reference to the ‘Ad Hoc Committee’ for 27 October, and the meeting that took place in Sheffield on 8-9 September (see part 1).

Tariq Ali, also later wrote:[20]Tariq Ali, Street-fighting memories, The Guardian, 1987.

| At every press conference during this period I had stressed that VSC did not want any violence and there would be none provided the police kept away from the march. Scotland Yard believed something sinister was being planned and increased Special Branch surveillance. I was followed almost everywhere, and the pub near the Black Dwarf offices was always full of Special branch men. |

Monitoring during September 1968

From September 1968, Dixon provided weekly Special Branch reports on the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign’s Autumn Offensive, a number of which are now available. They regularly show detailed knowledge of the political differences within the coalition, and in the weeks in the immediate run up to the demonstration of the 27 October provided details of the plans of individual groups.[21]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, weekly summary, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

On 10 September, Dixon provides an extensive report on the VSC and its plans.[22]Conrad Dixon, Report on Vietnam Solidarity Campaign “Autumn Offensive”, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 10 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). It gives a bit of historical background to the protests, the differences between the groups involved and bits of internal politics, particularly around the issue of violence. Though there are mistakes, enough of it is true enough to indicate well-placed sources and some depth of understanding of the campaign’s internal issues and structures.[23]A comparison of the material in this report against that outlined in Part 1 of this article shows a strong overlap. Ernest Tate, as noted, has taken issue with this, and we have found other mistakes – eg. Edward Davoren was with the RSSF and not the Radical Student Alliance – but the material is substantively correct to a degree and not otherwise openly published that we have discovered in the available campaign and group literature of the time, though it has emerged in articles and books in later years.

It is at this point also that the available reports begin listing alternative targets suggested by the various campaign groups. Dixon writes:

| It will be appreciated that many of these “targets” have been put forward by individuals, or minority groups, who lack the ability to carry out these rather grandiose proposals… |

which indicates that at least some of the material comes from people present at meetings.

The last three of the weekly reports from October also provide a list of ‘new “targets” mentioned during the last week’, indicating the intelligence was being collected in real time, probably in part from the SDS undercovers that would have been deployed by this stage.[24]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 9 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).[25]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, weekly summary, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).[26]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” weekly report, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 22 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

The founding of the Special Demonstration Squad

The book, Special Branch – A History 1883-2006, written by two former Special Branch officers, one of whom appears to have served with the Special Demonstration Squad,[27]Ray Wilson is named in other Special Branch documents, relating to an investigation into Black Dwarf in October 1968. See part 5 for details. gives some background on the founding of the unit:[28]Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, Biteback Publishing, 2015.

| After the lawlessness accompanying the demonstration in March, the Home Office, in consultation with the Commissioner [John Waldron], decided that better prior intelligence as to the likely course of events on that chaotic afternoon would probably have prevented many of the worst incidents.[…] The Commissioner directed that a special section within MPSB should be created with the specific role of assimilating themselves with potential protesters and gathering intelligence on their likely tactics, the numbers expected on demonstration and the identities of core militants. This initiative was supported by the Home Office, who provided direct and dedicated funding. |

Twelve Special Branch officers, from constable to chief inspector level are taken by the Head of MPSB, Commander Ferguson ‘Fergie’ Smith to see the Assistant Commissioner for Crime, Peter Brodie.[29]Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, Biteback Publishing, 2015.

| His message was simple: ‘Find out what these people are planning for 27th October’. Back in his office, Fergie was unable to elaborate, except to warn his officers against acting as agent provocateurs” and to take care not to become elected to office in any of the organisations they succeeded in joining. |

This was the founding of the Special Demonstration Squad (known in its first four years as the Special Operations Squad), placed under the control of Det. Ch. Insp. Conrad Dixon. According to the book Undercover, it was September 1968 when Dixon proposed the idea of the SDS to his bosses.[30]Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013.

Dixon’s report of 3 October 1968 sets out the leading groups organising for the protest of the 27th October, the likely targets of the embryonic SDS. As well as the VSC generally and the RSSF, these included the Anarchist Communist Federation (and several smaller anarchist groups), the Communist Party / Young Communist League, Maoist groups such as the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front (spearheaded by the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League) and the communist-led Radical Students Alliance. Other groups active at the time were the Australian and New Zealanders Against the Vietnam War, and the American expatriate campaign “Stop-it” Committee – where one leading campaigner had a particularly strong link to Camden / Hampstead VSC (see part 4).[31]Conrad Dixon, VSC “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 3 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK). Longer standing peace groups were also monitored, though they had a lesser role in organising for the day or declined to back the protest.[32]Conrad Dixon, VSC “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 9 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

Various writers active at the time have noted that much of the militancy of the 1968 protests came from the anarchist / Maoist sections of the anti-Vietnam War movement, and it was people from this political milieu who were at the forefront of several clashes in Grosvenor Square between protestors and police. In one of his weekly reports, Dixon noted that several VSC branches were ‘captured’ by Maoists and anarchists, leading to them being disowned by the national VSC. Given this, it is highly likely that the anarchists and Maoists were key targets of the SDS on its foundation, and again Dixon seemingly had inside intelligence on them. However, of itself, this is not confirmation that they were successfully infiltrated by undercovers at the time.

The presence of foreign protesters was also a matter of great interest, covered several times in the Special Branch reports in the run up to the 27 October protest.[33]Anti Vietnam war – files overview, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, undated (accessed 10 August 2017).

Many years later, the authors of the History of Special Branch concluded:[34]Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, Biteback Publishing, 2015.

| The efficiency with which, in 1968, the newly formed unit fulfilled their role in the comparatively short time at their disposal went some way towards ensuring that, on 27th October, the frontline troops had a better appreciation of the probable tactics that the ‘opposition’ might apply and could react accordingly. After the protest, it was decided that the SDS should remain in existence for the time being, and with the threat of violent mass demonstrations temporarily abated, Conrad Dixon had the opportunity to consolidate what had already been achieved.

By now, some members of the team had successfully infiltrated some of the more militant groups on the left, while other members were obviously not suited to this type of work and transferred to other duties. |

Intelligence gathering ahead of 27 October demonstration

The 23 September 1968 weekly report from Dixon is titled, ‘New Intelligence’, and contains considerable new material that indicates various sources of internal intelligence, albeit some of it could have been relatively easily obtained by attending open meetings of the groups mentioned. However, there are quite a few parts which give insight on the level of material being acquired, with the proviso that this is merely the police’s interpretation and may be a misrepresentation of what was actually said.[35]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 23 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

| New Intelligence

1. The national headquarters of the V.S.C. has issued a warning to all loyal branches that the Notting Hill Gate and Earls Court groups are no longer recognised by the parent body. The Earls Court branch has been captured by the Maoists, while the Notting Hill Gate branch has for some time been controlled by anarchists and Maoists. At a recent meeting in Notting Hill it was suggested that members attack American bank premises and barricade the streets on the 27th. 2. The North West London ad-hoc Committee has agreed to follow the official route as laid down at Sheffield, and members are making enquiries to ascertain the names and addresses of directors of firms engaged in contract work connected with the Vietnam War. The intention is to publish the information in left-wing journals after it has been passed to national headquarters. 3. Some young anarchists in West London are planning to change the names of Underground stations and broadcast anti-war messages on the loudspeaker systems on the 27th. Enquiries are in hand in conjunction with London Transport Police. 4. The South East London ad-hoc Committee has decided what actions members will take on the day. They are to assemble at Camberwell Green at 12 noon on the 27th, and then march by way of Camberwell Road, Walworth Road, Elephant and Castle, St. Georges Road, Westminster Bridge Road, and Westminster Bridge to the Embankment. When the main body reaches Trafalgar Square the South East London party will break off and go directly to Grosvenor Square, entering it by way of Brook Street. In the event of being dispersed they will rally again in Berkeley Square. 5. A new Maoist “front” organisation – the “October 27th Committee for Solidarity with Vietnam” – has been formed in the last few days. At the inaugural meeting on 19.9.68 the following suggestions were made:…. 6. The Anti-Imperialist Solidarity Movement also formed during the past week. It has very few members, but a cyclostyled leaflet, issued by the organisation gives the following “practical guides to conduct on the demonstration”… [there follows extracts from the leaflet which give practical advice for dealing with police brutality and cordons]. Urgent enquires are in hand about this organisation. |

This later organisation had been identified by the time of the 3 October report when it was associated with the anarchist milieu and in particular connected to Frank Farr, who had been an ambulance driver for the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War.

| Counter-measures 3. The V.S.C. have been making enquires at the Debden Caravan Site and the Crystal Palace Caravan Site to arrange accommodation for eighty foreign students from the 24th to the 31st October. We are keeping close touch with the wardens at these sites: all other caravan and camping sites within easy reach of the Central London area are being canvassed, and a report will be submitted immediately prior to the demonstration giving details of where groups of foreign students will be staying. |

It is presumed that this information came from the caravan site wardens themselves.

The 3 October 1968 weekly report details yet more new intelligence, focusing in part on reporting back on national developments relating to the 27 October protest, including picking up intelligence from a recent Anarchist Communist Federation conference in Liverpool.[36]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 3 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). The report contains a number of points of interest including:

| (d) The Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation continues to emphasise the importance of Australia House as a symbol of Commonwealth complicity in the Vietnam war and is calling for militant action there. Members of the group called Australians and New Zealanders Against the Vietnam War attempted to disrupt a social event at Australia House on 27.9.68. Police had advance warning of their intentions, and about a dozen people who tried to create a disturbance were escorted from the premises. All the indications are that a further attempt will be made at this building. |

This strongly indicates inside information being obtained, and we will return to this paragraph when examining the undercover John Graham. The report continues:

| (g) Arrangements are in hand to obtain an ambulance for the removal of wounded demonstrators. The Arts Laboratory at 128 Drury Lane, W.C.2. is to be used as a first aid station. |

Dixon concludes his report of 3 October by noting that though the VSC at committee level is dominated by Trotskyists, they are likely to be outnumbered on the day by supporters of other groups who are not represented at committee level, and who ‘have in their ranks the type of demonstrator who is most likely to use violence and to be hostile to the police’. In this he means the ‘Maoists, anarchists and foreign elements’. He concludes:[37]Conrad Dixon, VSC “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 3 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK).

| The Vietnam Solidarity Campaign is an uneasy coalition of warring factions and the [International Socialists] are aware of the “tail wagging the dog” aspect of the organisation. The more discerning of them have come to accept that Oct. 27th will be the last major demonstration by the V.S.C. in its present form. |

On 9 October, Dixon writes of the mood and behind the scenes work of the campaigners. In particular, he reports that there is ‘a growing mood of despondency in V.S.C. circles, and there is a tendency to clutch at straws’ as a result of CND declining to back the demonstration of 27 October and the Communist Party possibly doing likewise, both of which potentially took out significant contingents of numbers. He notes that the V.S.C. is trying to build numbers by reaching out to trade unions, albeit the response there is lukewarm and he also notes there is a ‘fatalistic view, common to almost all intending participants in the demonstration, that there will be serious disorder’. No judgement is made by us as to how accurate a representation of the VSC and various group organisers this is, and we have not seen material which supports this.

Dixon is also able to state that the VSC is running at a loss of £70 a month and is having to appeal for extra donations; it is not known what the source of this is.[38]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 9 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

As groups continue to settle on their plans, Dixon now reports on the specifics. Many branches in London were planning their own feeder marches into the main one. On 9 October he gives the route of the Camden Committee for Peace in Vietnam group (communist led).[39]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 9 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). Likewise, he details in his 16 October report the plans of the North West London ad hoc Committee of the VSC, along with that of the anarchists (who were to march behind a banner reading ‘United Libertarian Groups’). For the first time he links mentions of targets with the groups considering them – such groups being the anarchists and Syndicalist Workers Federation who favoured a protest at the Spanish Embassy, the RSSF targeting of the empty Centre Point office block at Charing Cross, and Lambeth VSC stickering of MI6’s headquarters on Westminster Bridge Road. (Lambeth VSC is strongly suspected, though not yet confirmed, to have had an undercover officer in it – see part 4). The report also mentions intentions by students from S.O.A.S. to carry out an occupation of their university on 25 October, similar to the plans of students at the LSE.[40]Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, weekly summary, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

There are two other points of interest from the 16 October report. First there is a listing of names prominent in campaigns around Vietnam; many could have been openly sourced, but from our examination of publications of the time, others are not so publicly named and would have only come from monitoring of the IMG, the International Socialists and local VSC groups, particularly ones in north west London. The second point is this curious paragraph, again hinting at intelligence from those close or inside the groups:

Among the documents released is a report of a meeting between ministers and the heads of newspapers on 17 October, which notes that though it was recognised that there was the distinct possibility of disorder from some groups on the day, for the most part the march was lawful, likely to be peaceful and so would not be banned. The ministers present and the Commissioner of the Metropolitan police spoke of their concern to avoid putting measures in place that might otherwise provoke or give cause to justify violence, such as restrictions on the march. It also sheds light on the police’s own preparations, demonstrating the large scale nature of the response:[41]Minutes of meeting between the Home Secrtary, Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis and Sir Philip Allen with newspapers proprietors, Metropolitan Police, 17th October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk).

| About 7,000 police officers would be on duty from the Metropolitan police force, and there was no need to call in help from neighbouring forces. Special Constables would be used in strength to look after police stations. There would be about 150 mounted officers; police horses were a traditional and effective means of control. A special mobile group would be active before the demonstration started. Dogs would not be used. For police officers there had been a certain amount of special training at Hendon [Police College] in the use of wedge techniques and in improving response speeds. the police would have no special or defensive equipment. Even the use of barricades in front of the United States Embassy would be too provocative. The communications system used by the police had been specially improved for the occasion. |

Curiously, the minutes conclude:

| The Commissioner [of the Metropolitan Police, Sir John Waldron] said this demonstration was likely to be the demonstration to end all demonstrations. The Home Secretary [James Callaghan] thought Vietnam was probably nearly exhausted as a subject for demonstrations but others would arise. |

Commentary of Ernest Tate

On reviewing the Special Branch material, Ernest Tate, who had been a leading organiser in the Vietnam Solidarity Group and a member of the International Marxist Group, wrote (taken from a much longer letter):[42]Ernest Tate, On the Secret Internal Police Reports about the 1968 mobilizations against the Vietnam war in in London, England (Letter from Ernest Tate to Solomon Hughes of 27 May 2008, Marxsite.com (accessed 22 August 2017).

| Every little tidbit of information, the gossip, the stupid speculations by un-named people, who could even be other plain clothes cops, the talk about cutting GPO lines setting vehicles on fire, etc., is just silly, and meant to put the wind up their superiors, I’m sure. Take the issue of violence, for example. In the report, “Vietnam Solidarity Campaign ‘Autumn Offensive’”, Sept. 10, 68, p3, it states: “The more cautious representatives of the International Socialism and International Marxist groups paid lip service to the vision of a peaceful demonstration.” This is written by someone who must have been asleep and had not been following what was going on, and it suggests that whoever they had planted inside, if it came from there, was somewhat inept, and collecting money under false pretences. Let me explain. It’s just not logical what the report says about this.

The International Marxist Group, of which I was one of the leaders, was very clear about what our objectives were: very simply, we wanted the Labour Government to break from the Americans on Vietnam. This would be the best way, we thought, to put pressure on the U.S. to withdraw their troops and the best tactic for accomplishing this was having tens, if not hundreds of thousands of people on the streets of London protesting. This is what we meant by solidarity with the Vietnamese and why we, along with the Bertrand Russell Foundation, set up the VSC. Some of VSC posters even carried the slogan calling for victory for the NLF. To achieve this, we had to make it possible for ordinary people to come out onto the streets and protest peacefully. A deliberate policy of seeking out confrontation and fighting the police stood in the way of this. At a special VSC conference in early 1968, after a very brief stay, most of the Maoist groups – especially Albert Manchanda – broke from the VSC, strange as it may seem, because we had refused to adopt their proposal to endorse the programme of the Vietnamese National Liberation Front. It was their way of trying to tie us into the politics of the NLF, and the Maoism of the Communist Party of China. It was in the Ad Hoc Committee where we had the strongest debates about violence and confrontation, especially around the question of a possible route for the October 1968, action. It seems whoever was writing the reports, was totally unaware of this. |

[2. History of the VSC and the protests of 1968] [Return to Intro] [4. Infiltration by the Special Demonstration Squad]

References

| ↑1 | For an overview of the Special Demonstration Squad, see: Special Demonstration Squad, Powerbase.info, 2013 (accessed, 10 March 2018). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For an overview of Domestic Extremism as a concept, see: Peter Salmon, Domestic Extremism, Powerbase.info, 2015 (accessed, 10 March 2018). |

| ↑3 | Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, BiteBack Publications, 2015. |

| ↑4 | Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5, Penguin, 2009. |

| ↑5 | Rupert Allason, Branch: A History of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch 1883-1983, Secker & Warburg, 1983 |

| ↑6 | Robert Fleming & Hugh Miller, Scotland Yard: The True Life Story of the Metropolitan Police, Signet Books, 1994. |

| ↑7 | Conrad Dixon (obituary), The Times, 28 April 1994 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK). |

| ↑8 | Special Branch report in relation to Youth Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, Metropolitan Police, 24 March 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk) |

| ↑9, ↑42 | Ernest Tate, On the Secret Internal Police Reports about the 1968 mobilizations against the Vietnam war in in London, England (Letter from Ernest Tate to Solomon Hughes of 27 May 2008, Marxsite.com (accessed 22 August 2017). |

| ↑10 | Peter E Brodie, Letter to regional police forces requesting information on extremists planning to attend the anti-Vietnam War protest of October 1968, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 14 August 1968, (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑11 | Conrad Dixon, Special Branch report on Vietnam Solidarity Campaign’s “Autumn Offensive”, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 21 August 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑12 | Conrad Dixon, Report on Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 30 August 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK). |

| ↑13 | Tariq Ali explains the writing on the wall, The Guardian, 4 September 1968 (accessed 10 February 2018). |

| ↑14, ↑17, ↑18, ↑20 | Tariq Ali, Street-fighting memories, The Guardian, 1987. |

| ↑15 | Letter of Commander John Smith to the Home Office 5 September 1968 including a report from Conrad Dixon relating to various press reports on preparations for the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign Autumn Demonstration due to be held on 27th October, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 5 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK). |

| ↑16 | The report authored by Dixon is quite possibly drawn up in response to a Home Office request for a briefing on lurid stories then circulating in the media regarding the plans for the October demonstration. |

| ↑19 | Clive Borrell & Brian Cashinella, Callahan faces plot questions, The Times, 6 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑21, ↑25, ↑40 | Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, weekly summary, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑22 | Conrad Dixon, Report on Vietnam Solidarity Campaign “Autumn Offensive”, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 10 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑23 | A comparison of the material in this report against that outlined in Part 1 of this article shows a strong overlap. Ernest Tate, as noted, has taken issue with this, and we have found other mistakes – eg. Edward Davoren was with the RSSF and not the Radical Student Alliance – but the material is substantively correct to a degree and not otherwise openly published that we have discovered in the available campaign and group literature of the time, though it has emerged in articles and books in later years. |

| ↑24, ↑38, ↑39 | Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 9 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑26 | Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” weekly report, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 22 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑27 | Ray Wilson is named in other Special Branch documents, relating to an investigation into Black Dwarf in October 1968. See part 5 for details. |

| ↑28, ↑29, ↑34 | Ray Wilson & Ian Adams, Special Branch A History: 1883-2006, Biteback Publishing, 2015. |

| ↑30 | Rob Evans & Paul Lewis, Undercover: The True Story of Britain’s Secret Police, Faber & Faber, 2013. |

| ↑31, ↑37 | Conrad Dixon, VSC “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 3 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.UK). |

| ↑32 | Conrad Dixon, VSC “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 9 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑33 | Anti Vietnam war – files overview, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, undated (accessed 10 August 2017). |

| ↑35 | Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 23 September 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑36 | Conrad Dixon, V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive” (weekly report), Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 3 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑41 | Minutes of meeting between the Home Secrtary, Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis and Sir Philip Allen with newspapers proprietors, Metropolitan Police, 17th October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |