Rosie Wild and Eveline Lubbers, 17 September 2019

[Black Power – 1. Overview ] [Black Power – 3. Special Branch files in context] [Black Power – 4. Black Power Desk][Black Power – 5. Files overview, and another FoI battle]

Before we discuss Special Branch and Black Power, here are some detailed profiles of the most significant London-based Black Power groups. The groups are: the Universal Coloured Peoples Association (UCPA); Black Unity and Freedom Party (BUFP); Black Panther Movement (BPM); Black Liberation Front (BLF); Fasimbas; Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS). Included as well as the – mainly white – solidarity groups Black Defence Committee (BDC) and its Black Defence and Aid Fund.

Universal Coloured People’s Association

The UCPA was founded on 5 June 1967 at a meeting of 76 people in Notting Hill. Many of those first members had been meeting regularly at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park for months. The founding members agreed to pay membership dues and elected Nigerian playwright Obi Egbuna as their president and Roy Sawh as his second in command.[1]Information taken from the document ‘Names and addresses of financial members of UCPA’, held in Tony Soares’ private collection. Sawh and Egbuna did not work well together though, and by September 1967 Sawh and his supporters had left to form a tiny splinter group, the Universal Coloured People and Arab Association (UCPAAA). The UCPA continued to be riven by in-fighting between members with different ideological approaches, however, and in April 1968 Egbuna also left to start the more disciplined and hierarchical Black Panther Movement. In July 1970 the entire organisation split, with the bulk of the members reforming as the Black Unity and Freedom Party.

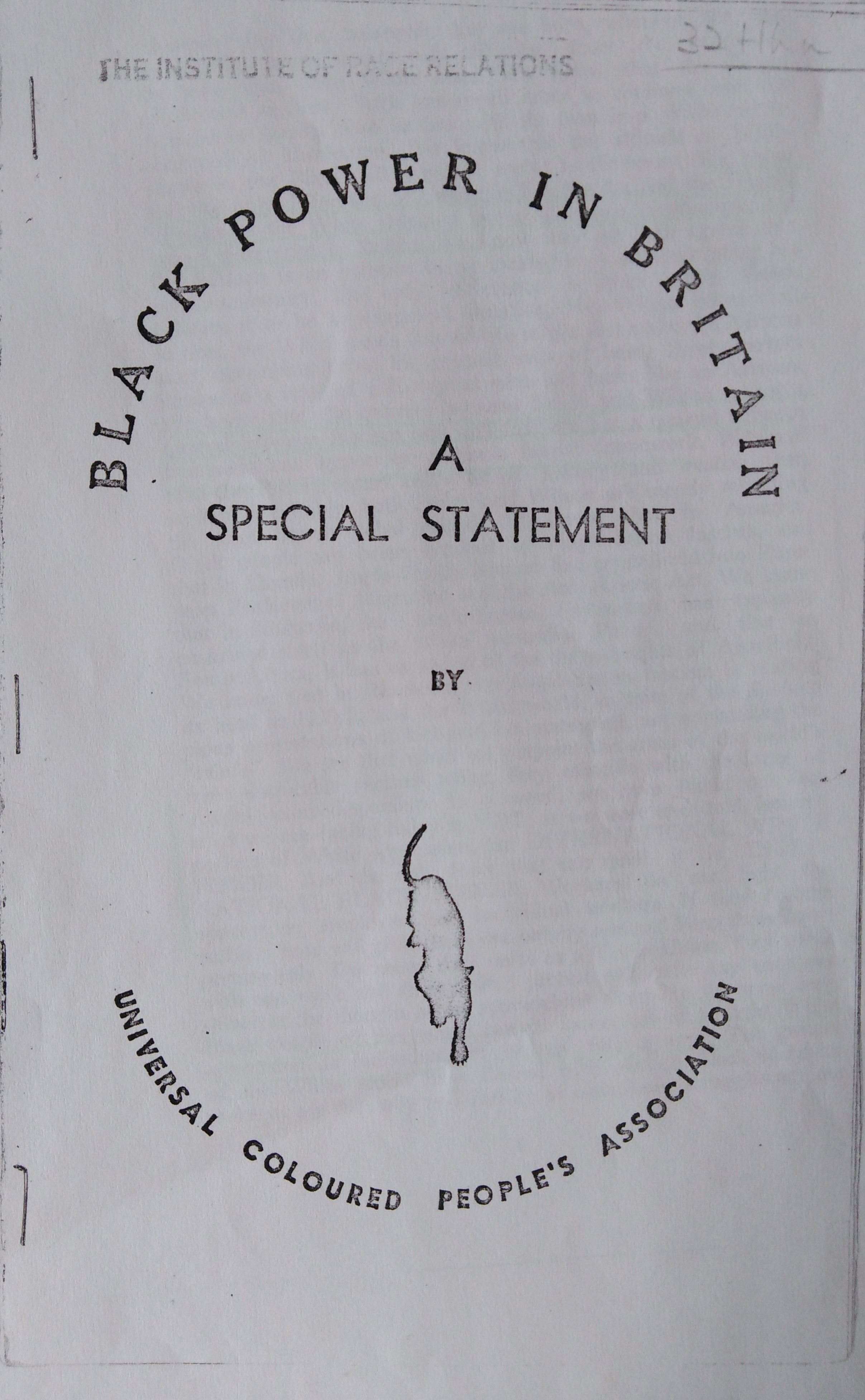

In September 1967, the UCPA set out its philosophy in a fifteen-page pamphlet called Black Power in Britain: a Special Statement by the Universal Coloured People’s Association.[2]UCPA, ‘Black Power in Britain: a Special Statement by the Universal Coloured People’s Association’, 10 September 1967. Featuring a drawing of a black panther on the front and a photo of Stokely Carmichael on the inside back cover, the pamphlet borrowed heavily from both the style and content of American Black Power. Its critique of white, capitalist society was derived, however, from a disillusioned analysis of contemporary British politics. ‘We know that the only difference between the Ian Smiths and the Harold Wilsons of the white world is not a difference in principle but only a difference in tactics,’ the pamphlet proclaimed, ‘it is not a quarrel between fascism and anti-fascism, but a quarrel between frankness and hypocrisy within a fascist framework.’[3]Ibid., p. 4.

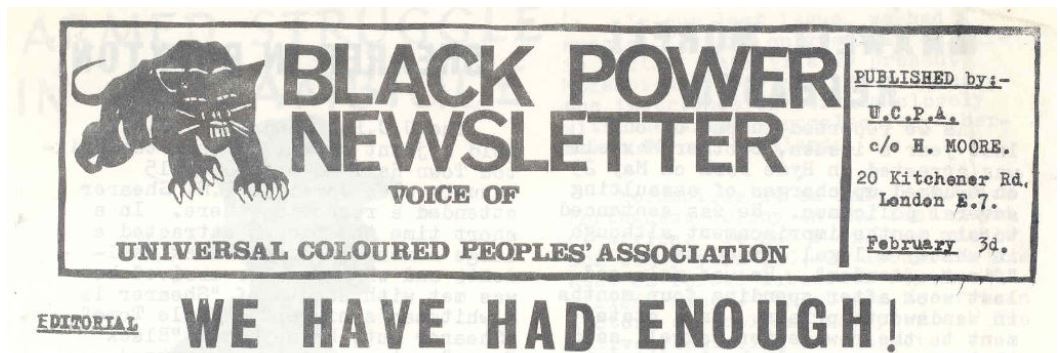

The UCPA’s activities consisted of weekly discussion groups, ‘work sessions’ in which members were taught skills such as ‘canvassing, duplicating, poster-making, anti-thug patrols etc.’, film screenings, public meetings, demonstrations, door-to-door and street-corner canvassing and, from late 1969, the production of a newspaper, the Black Power Newsletter.[4]This followed on from the short-lived Black Power Speaks, which came out monthly between May and July 1968 and was edited by Obi Egbuna. Cultural activities included events such as ‘Black Is Beautiful’, a free night of ‘soul music, poetry, films and recordings on black culture’, held at Lambeth Town Hall, while the Newsletter featured inspirational poems and satirical cartoons.[5]UCPA flyer, February 1967.

UCPA flyers show that the group mobilised its members to demonstrate in support of a wide variety of causes, from the republican movement in Northern Ireland to the Black Panther Party in California, and its newspaper charted the events of the Vietnam war and the progress of the African liberation movements, alongside reports on British and American Black Power activity. It also involved itself in domestic politics in a more direct way by urging its members to vote tactically against Conservative candidates during the 1970 general election, on the basis that ‘Labour is the lesser of two evils’.[6]See undated UCPA flyer, ‘A message to black voters’.

Although started in London, the UCPA aspired to create a national network of loosely federated branches. Its biggest branch outside of London was in Moss Side, Manchester. Led by Ron Phillips (brother of Trevor and Mike), it published its own edition of the Black Power Newsletter. White people were not allowed to join the UCPA, but Tony Soares was one of several Asian men who signed up. A UCPA leaflet entitled ‘Black Power is Black Unity’ defined black people as ‘Africans, West Indian, Indians, Pakistanis, Chinese, Arabs and all non-white peoples’.[7]UCPA, ‘Black Power in Black Unity, undated leaflet.

Members also came from diverse economic backgrounds and, according to Soares, ‘There wasn’t any particular class distinction or class consciousness.’[8]Tony Soares, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 23 August 2004. It was eventually this lack of emphasis on class struggle that led the organisation’s more Marxist-leaning elements, led by George Joseph and Communist Party member Alrick (Ricky) Cambridge, to campaign to restructure and rename the organisation in the summer of 1970.

Black Unity and Freedom Party

The BUFP was formed from the remains of the UCPA at a conference on 26 July 1970. Former UCPA member George Joseph was elected its general secretary and its two branch headquarters in London and Manchester remained at the same addresses as the former UCPA offices. The BUFP described its ideology as ‘Marxist-Leninist with Mao Tse Tung thought’, according to former member Lester Lewis.[9]Lester Lewis, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 14 September 2004.

As befitted a Marxist-Leninist organisation, the BUFP strove to become more disciplined and implemented a strict hierarchy and rules of membership. There is conflicting evidence on whether the BUFP allowed white people to join. While the BUFP’s politics meant it did not define the white working class as the ‘enemy’ of the black working class, it stated that the ‘contradiction’ of white working class racism meant white and black workers were not yet ready to make common cause. The BUFP’s definition of black included Asians and it actively sought solidarity with groups like the Indian Workers’ Association of Great Britain.

The BUFP’s manifesto included eleven demands for government reforms, among them a public enquiry into racism in the police, better treatment of black people by immigration officers, repeal of the 1968 Race Relations Act, trial of black defendants by black juries and judges, the release of all black prisoners who had not been tried by their ethnic peers and more black history on the school curriculum’.[10]‘Black Unity and Freedom Party Manifesto’, 26 July 1970.

Like the UCPA before it, the BUFP organised discussion groups, demonstrations, produced pamphlets and campaigns on domestic issues like the 1971 Immigration Act and in support of African liberation struggles in Angola, Guiné, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa. From August 1970, the BUFP also began publishing a newspaper, Black Voice, which replaced the Black People’s Newsletter.

‘There were some interesting organisational overlaps between the BUFP and white left-wing groups. General Secretary George Joseph was – with another key figure in the BUFP – a member of the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front (INLSF).[11]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 p61 (accessed February 2019). The two groups came together under the banner of the ‘Anti-Fascist Revolutionary Coordinating Committee of National Minorities’ through which they organised joint protests,[12]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).[13]A black worker stands on picket in condemnation of British imperialist atrocities in Ireland, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). and in July 1971, the conference of the BUFP adopted a resolution on Solidarity with the people of Ireland.[14]Black Workers wholeheartedly support their Irish class brothers and sisters, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

For more on this cooperation, see the article Special Branch and the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front.

Another group that was very active in engaging radical left groups with the black struggle was the Troskyist International Marxist Group. See below, in the section on the Black Defence Committee.

The BUFP continued to exist and publish an increasingly professional-looking Black Voice well into the 1990s, but it had long stopped identifying itself with Black Power. Black Voice dropped the phrase ‘Power To The People’ from its masthead at the start of 1973 and its reporting on the Spaghetti House Siege in 1975 referred only to the ‘Black movement’ or ‘Black struggle’ and described the BLF, BUFP, Fasimbas and various other groups simply as ‘Black organisations and black community workers’.[15]The last time ‘Power to the People’ appeared on a Black Voice masthead was volume 4, number 1, which given the subjects of the articles, one can deduce was published at the start of 1973. See also, ‘The truth about the Spaghetti House Siege’, Black Voice 5:3 (1975), back page.

The Black Panther Movement

The Black Panther Movement (BPM) was started by Obi Egbuna in Notting Hill, London, in April 1968. Inspired by, but not affiliated to, the American Black Panther Party, initially it had only a handful of members. Egbuna was not active in the BPM for long. In July 1968 he was arrested for publishing a pamphlet titled, ‘What to do if cops lay their hands on a Black man at the Speaker’s Corner’ after its printer – possibly an informant – turned a copy over to the police.[16]See Metropolitan Police file MEPO 2/11409: ‘Benedict Obi Egbuna, Peter Martin and Gideon Ketueni T. Dolo charged with uttering and writing threats to kill police officers at Hyde Park, W2’, held at the National Archives (NA). Held on remand for five months, Egbuna was convicted in December 1968 under the Offences Against The Person Act, 1861, and sentenced to a year in jail, suspended for three years.

Cowed by the conditions of his sentence, which prevented him from engaging in radical political activity, Egbuna curtailed his career as a Black Power leader and Altheia Lecointe, a Trinidadian postgraduate student, became the Panthers’ new leader. After Egbuna’s departure the organisational centre of the BPM moved from Notting Hill to Shakespeare Road in Brixton and separate branches were started in Acton and Finsbury Park.

The BPM was a secretive organisation and required potential recruits to show their dedication before they were nominated for membership. Once in, being a Black Panther was a way of life rather than a political affiliation. Members underwent rigorous ideological training and were supposed to adhere to a strict moral code.

Culture was an important focus. ‘It was part of our ideology that culture and politics worked together hand in glove in a culture of resistance’ explained former Panther Linton Kwesi Jonson.[17]Linton Kwesi Johnson, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 17 September 2004. Black Panthers toured youth clubs and arts centres lecturing black teenagers about their history and Johnson ran cultural workshops for the Black Panther youth league. The BPM hosted events that often attracted audiences of several hundred people. Police notes on a raid of a Black Panther carnival at the Oval House in South London on 31 August 1970, for example, record that 400 people were present.[18]See DPP2/4890: ‘Rupert James Frank, Leonard Anderson, Edmund Lecointe and Keith Spencer (Black Panther Movement members) riot and incitement on August 31, 1970 in SE11. Convicted’ at the NA.

The dedication required to become a Black Panther meant that the branch membership remained in the tens, but hundreds could be mobilised for demonstrations. A 1968 Metropolitan Police report that estimated the number of British Black Panthers at more than 800 did not comprehend the difference between members and supporters.[19]See MEPO 2/11409, p. 2.

BPM members included Africans, Asians and African Caribbeans, notable among them: Faroukh Dhondy, Tony Soares, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Altheia Jones-Lecointe, Barbara Beese, Olive Morris, Neil Kenlock and Darcus Howe. The BPM was prepared to accept support from radical white organisations but white people were not allowed to join or come to meetings. It did, however, publicly proclaim solidarity with the struggle of Irish republicans against British occupation and striking British miners.

The BPM had always believed that racial equality was not possible under a capitalist imperialist system and instructed its members not to bother participating in electoral politics.[20]See BPM flyer ‘Black People Don’t Vote: organise against exploitation and British institutional racism’, June 1970. By the 1970s, it had moved to the position that class revolution was the only solution to the problem of racial discrimination, bringing it closer to the position of the BUFP.

By the early 1970s the internal organisation and discipline of the BPM, always strict, became intolerable in the opinion of many members. Darcus Howe described the central committee as ‘Stalinist type. It was built on the same structure as the Bolshevik Party, it was a kind of vanguard party organisation’.[21]Transcript of an unpublished interview with Anne Walmsley on 16 January 1986, p. 4. The transcript is part of the Caribbean Artists Movement papers held at the George Padmore Institute. Tony Soares believed that, by 1970, ‘the BPM was … being increasingly controlled by the Marxist elements: black Trotskyites, Socialist Labour League, the International Marxist Group. … They had come in and were basically running the show and the people were not comfortable with that’.[22]Tony Soares, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 23 August 2004.

Soares, along with all the other members of the North and West London branches, left the BPM in protest in 1970. In June 1973, the BPM changed its name to the Black Workers’ Movement: the defection of so many members and the accusation of being in thrall to white Marxist organisations had taken the Movement far from its Black Power roots

The Black Liberation Front

The Black Liberation Front was founded at the start of 1971 by former members of the North and West London branches of the Black Panther Movement. Its headquarters were at 54 Wightman Road, formerly the BPM’s North London branch address. The BLF maintained close links with the Black Panther Party in the United States and was organised on the same lines, with separate divisions for areas such as self-defence, propaganda and youth.

Having split from the BPM because of its rigid Trotskyism, the BLF was non-hierarchical and took its political lead from Maoism. It was also pan-Africanist: BLF members attended the 6th Pan African Congress in Dar-es-Salaam in 1974 and a 1975 issue of Grass Roots announced that the BLF was a member of the Pan African Committee (U.K.) and that it ‘work[ed] closely with the liberation movements of Southern Africa’.[23]‘B. L. F. Projects’, Grass Roots 4:1 (1975), p. 15.

The BLF represented the most cultural-nationalist vein of Black Power thought and was sympathetic to Maulana (Ron) Karenga’s US organisation in America. The BLF’s cultural nationalism also sprang from a grave disillusionment with white society at all levels, exacerbated at the time of its founding by the passage of the 1971 Immigration Act. Describing Britain as a ‘fascist lunatic asylum’, one BLF leaflet explained that white Britons ‘[D]on’t mince words any more. They are giving it to us straight. They hate us because we are black and they are gunning for us’.[24]‘B. L. F. Projects’, Grass Roots 4:1 (1975), p. 15.

The BLF welcomed Asian members but, unlike the BPM and BUFP, saw no benefit in collaborating with radical white groups. ‘[Our] so le concern is survival for Black people in Britain and socialism in their homelands’ announced an editorial in Grass Roots[25]Undated BLF leaflet from Tony Soares’ private collection. This separatist perspective meant that the BLF focused entirely on organising within the black community and withdrew from activities such as demonstrations that were intended to provoke a response from the white community.

Youth work was given particular prominence. Boosting black children’s knowledge of their own culture and history was the major focus of the BLF’s youth wing, the Black Berets, which along with later group, the Makonde Youth Club, met as many as three times a week to play sports, do drama, watch films, learn karate and even go to discos. On Sunday mornings until the end of 1972, the BLF’s North London headquarters was also home to the independently-run Headstart supplementary school.

Discussions for adult BLF members were held on Sunday evenings, on Friday nights a two-hour drop-in advice service for local black people was provided. Three community bookshops were also started by the BLF – two Grass Roots Storefronts, at 54 Wightman Road and from December 1972 on Golborne Road in Notting Hill, and a Headstart Bookshop in West London.[26]Information from interviews and email correspondence with Tony Soares. A list of BLF activities from a 1974 Grass Roots also lists the ‘Ujima Housing Association’, providing affordable housing to black families and a ‘Prisoner’s Welfare Committee’ which corresponded with and visited black prisoners.[27]See ‘BLF activities’, Grass Roots 3:3 (May 1974), p. 2. Ujima was still in existence in the 21st century.

Outside of the black community the BLF was best known for its newspaper Grass Roots, which was edited by a variety of different people including Tony Soares and Ansel Wong. Started in mid-1971, by its third issue, Grass Roots was being distributed in Bristol, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Bradford, Liverpool, Hull, Sheffield and London.[28]Information on the national distribution of Grass Roots provided by Tony Soares.

Its fourth issue, circulated in September 1971, contained a reproduction of a page from the American Black Panther Party newspaper, which featured instructions on how to make a Molotov cocktail. Although The Black Panther, from which the ‘recipe’ was taken, was legally available in radical book shops and even some libraries, and Tony Soares was not its editor at the time, in March 1972 he was charged with attempted incitement to arson, bomb-making, possession of a firearm with intent to endanger life and murder of persons unknown – all potentially punishable by life imprisonment. Held on remand for four months before being released on bail, he was eventually tried at the Old Bailey in March 1973 and convicted of inciting arson and the manufacture of explosives. Extremely surprisingly, given his former conviction for a similar offence, for which he was sentenced to two years in prison, and the extremely hostile attitude of judge Alan King-Hamilton throughout the trial, Soares was only sentenced to 200 hours’ community service.

The Black Liberation Front hit the headlines again, in October 1975, when three young black men claiming to be part of the Black Liberation Army, a supposed adjunct of the BLF, attempted to rob the Spaghetti House restaurant in Knightsbridge and ended up taking eight members of its staff hostage for five days. As the BLF had no official membership procedure it was impossible to prove or disprove their claim, but the organisation issued a statement of support. The BLF continued to champion the cause of Black Power in Grass Roots after 1975 but its increasingly shrill and paranoid editorial line made it an extremely niche publication. Tony Soares left the organisation in 1977, feeling it had run its course.

Fasimbas

The Fasimbas, formerly the youth wing of the South East London Parents Organisation (SELPO), was based in Lewisham, London.[29]Most of the information on the Fasimbas in this paragraph comes from former activist Winston Trew’s self-published memoir Black for a Cause (Derbyshire, 2010). pp. 186-7. An independent organisation from Spring 1970, it was influenced by Marcus Garvey and governed by committee. Fasimbas members provided community services such as free plumbing, self-defence classes, supplementary education and legal advice as well as putting on plays and producing and distributing literature about African history and culture and Black Power politics. The Fasimbas had around 500 members, according to BLF activist Tony Soares, and worked closely with his organisation, eventually merging with the BLF at the end of 1972.[30]The 1972 merger of the Fasimba and the BLF is reported in a potted history of the BLF in Grass Roots, 4:4 (January 1976), p. 2.

Winston Trew was a member of the Fasimbas whose commitment to Black Power politics cost him dearly. Travelling home on the tube after a meeting of the Tony Soares Defence Fund on 16 March 1972, Trew and three fellow activists were confronted by a group of white men who accused them of stealing handbags and attacked them. After Trew and his friends resisted, the white men announced that they were undercover transport police officers and arrested all four for robbery and assaulting a police officer.

Trew has always believed that the Fasimbas must have been under surveillance by Special Branch and that it was no coincidence that he and the other members of the ‘Oval Four’ were targeted by undercover officers that day. Their trial at the Old Bailey in November 1972, which lasted five weeks, was widely reported on because of its political significance, but ultimately the jury convicted all four, largely based on their forced confessions. They received custodial sentences of two years, which were later reduced to eight months on appeal. All four spent several months in prison and even though Trew later went to university and had a successful career as a sociology lecturer, his conviction cast a long shadow over his life.

The leading officer who arrested the Oval Four was Detective Sergeant Derek Ridgewell. Convicted of theft himself later on, he died in prison in 1982. Judicial concerns about Ridgewell’s behaviour had surfaced as early as 1973 when a very similar case as that of the Oval Four was thrown out of court.[31]The Tottenham Court Road Two were a pair of Jesuit students from Oxford University accused of mugging tube passengers by Ridgewell and arrested at Tottenham Court Road tube station. It was not until 2017, however, when another young man Ridgewell had falsely accused in the 1970s asked the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) to revisit his conviction in the light of Ridgewell’s criminal conduct that anyone thought to re-examine the large number of young men who had been sent to prison on Ridgewell’s evidence.[32]Duncan Campbell, How a ‘bent’ policeman could be key to clearing a man’s name, 40 years on, The Guardian, 28/8/2017, accessed 24/2/20.

Winston Trew, who had written about Ridgewell’s criminal past in his 2010 book Black For A Cause was delighted to finally have the attention of the CCRC. In December 2019, 47 years after their conviction, he, Sterling Christie and George Griffiths had their convictions overturned by the Court of Appeal.[33]Duncan Campbell, ‘Oval Four’ men jailed in 1972 cleared by court of appeal in London, The Guardian, 5/12/19, accessed 24/2/20. Constantine Boucher, the fourth member of the Oval Four, who could not be located in 2019 has since been found and had his conviction overturned in March 2020.[34]Duncan Campbell, Final Member of the Oval Four has 1972 Conviction Overturned, The Guardian, 24/3/20, accessed 22/5/21.

Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS)

RAAS was accorded a significance during its six-year lifespan out of all proportion to its tiny membership and limited organisational achievements. It was founded in May 1965 by Trinidadian immigrant Michael de Freitas, who claimed to have been inspired to start his own organisation after hearing Malcolm X speak at the London School of Economics. De Freitas was charismatic, intelligent and a master media manipulator but also unpredictable. He had previously worked as an enforcer for infamous slum landlord Peter Rachman. Present during the Notting Hill riots of 1958, he had been active in various civil rights groups that were started as a reaction to the unchecked violence against black people during the riots.

Michael X explicitly cultivated comparisons with Malcolm X, but the two shared very few qualities: Michael was more interested in the image of Malcolm than the substance of his politics. By the time of Stokely Carmichael’s visit in July 1967, RAAS had long been little more than a media vehicle for Michael X and he was regarded by many of his non-white contemporaries as, in Linton Kwesi Johnson’s words, ‘a charlatan’.[35]Linton Kwesi Johnson, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 17 September 2004.

The heavy handed actions of the British state changed all that. In September 1967 Michael X’s reputation in the black community was significantly resuscitated when he became the first non-white person to be tried for inciting racial hatred after a fiery speech he had given in Reading that July, as a last minute stand in for Stokely Carmichael. Convicted on 9 November 1967, he served eight months of a one-year prison sentence and was released in July 1968 to a martyr’s welcome.

For a year after his release Michael X held the position of Minister of Defence for a small London-based cadre of Black Panther-style activists called The Black Eagles, led by ‘Prime Minister’ Darcus Awusu, aka Darcus Howe. At the start of 1969, with the financial backing of white publishing heir Nigel Samuel, RAAS bought the buildings at 95–101 Holloway Road in order to turn them into a cultural centre, shopping complex and hostel called The Black House.

Conceptualised as a project run by and for the black community, The Black House attracted funding from people and organisations that would otherwise have avoided association with a Black Power organisation. CND founder Cannon Collins, anti-apartheid campaigner Bishop Trevor Huddleston and the World Council of Churches all donated funds, as well as celebrities Sammy Davis Jr, Muhammad Ali and John Lennon.

Although the Black House project and particularly Michael X’s leadership of it was, at best, deeply flawed, it provided an important source of inspiration to other, more committed people, who joined its staff. It also served a useful function as a meeting place and organising space for local black groups. Nonetheless, the project was derailed in 1970, first by a suspicious fire in January 1970 that the police concluded was a result of arson and then by the arrest of Michael X and seven other RAAS members in April, following allegations of robbery and assault by businessman Mervin Brown.[36]See MEPO 31/4: ‘Malik, MA, alias Michael X, of the Racial Adjustment Action Society: complaints of intimidation, victimisation and harassment by police following a raid on the Society’s headquarters, the “Black House”, 95-101 Holloway Road, N7 on 17 April 1970. Malik and others arrested for robbery and blackmail 1970-1971’, held at the NA.

At the end of November 1970 Michael X resigned from RAAS and in February 1971 moved to Trinidad to avoid facing trial for the charges relating to his April 1970 arrest. The British government declined to seek an extradition order for his return.[37]See FCO 63/613: ‘Black Power movement in Caribbean’, held at the NA. Trinidad did not prove to be a safe haven for Michael X for long. In 1972 he was convicted of the murders of two of his followers, Gale Benson and Joseph Skerritt, crimes for which he was hanged in May 1975.

Solidarity organisations: Black Defence Committee and the Black Defence and Aid Fund

The Mangrove demonstration in August 1970 and subsequent October to December 1971 trial were important catalysts for others – i.e. white people – on the radical left to reorientate their own politics through a black radical perspective.

The Trotskyist International Marxist Group (IMG), however, had been active on this front for some time. The IMG’s fortnightly magazine Red Mole regularly called out police harassment against black comrades, at Irish solidarity demonstrations, for instance, where the police specifically attacked the black people attending.[38]Red Mole, Vol.1. No.1 March and No.8, August 1970. IMG also joined the Black Panther demo of 31 May 1970.[39]Red Mole, Special Election Broadsheet, ca. 1970 A demonstration against US imperialism in Vietnam and Trinidad on 26 April 1970 organised by the Vietnam Solidarity Committee and the Black Panthers amongst others ended in violent confrontations and arrests; according to Red Mole police ferocity particularly focused on black protesters, with further arrests after they appeared in court the next day. Red Mole carried an appeal of the ‘Black People’s Legal Aid and Defence Fund’ in support of the 20 mainly black people arrested.[40]’Donations to A. Williams, 3 Hornsey Rise Gardens N.19′, in Red Mole, Vol. 1, No.6, 1-14 June 1970. It is unclear if and how this fund relates to the Black Defence and Aid Fund to support the Mangrove Nine Trial discussed below. The July 1970 issue included an article on the release of Tony Soares, while the next issue had an interview with him on militant political organising among black people.[41]Red Mole, Vol. 1, No.7, July and No.8, August 1970. One of the founders of the BUFP, George Joseph, wrote for Red Mole on occasion.[42]George Joseph, ‘Trinidad’, Red Mole, 1. 5 (14 May 1970), p. 9[43]According to Special Branch, when George Joseph was elected treasurer of the UCPA, he was also a member of the International Marxist Group. The Special Branch report cites the membership to make the point that the UCPA seemed to be moving towards a more Trotskyist position after the imprisonment of Tony Soares in February 1969 and the expulsion of Harold Moore, both Maoists. (See the listing for the Universal Coloured People’s Association in Appendix A, “Black Power” Organisations in the United Kingdom’ of the Special Branch report “Black Power” in the United Kingdom, 1970, in HO 325/143, held at the National Archives.) We have not been able to find confirmation of Joseph being a member of the IMG, nor for him being elected as treasurer. While the UCPA was indeed full with ideological rifts, the BUFP co-founded by Joseph from the remains of the UCPA in mid 1970 identified as Maoist – as was pointed out above. (As was mentioned, Joseph was also a member of the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front, a Maoist group.) Though not entirely impossible, the IMG membership in 1969 seems highly unlikely.

After the arrests following the Hands Off the Mangrove march the IMG’s youth organisation, the Spartacus League, called on solidarity with the people arrested. In Red Mole, they condemned the ‘orchestrated hysteria against “Black Power extremists” in the press’ and ‘the large-scale intimidation and arrests of militants’. The Spartacus League organised a picket at the Court on 9 October 1970, and a tour around the country for the Black Panther Movement.[44]Red Mole, Vol. 1, No. 11, November 1970)

Also in October 1970, Tariq Ali – amongst others – set up the Black Defence Committee (BDC) as ‘a militant group to counter racist and fascist activities,’ based in the offices of the IMG. Its initial march, on 31 October 1971, followed the route of the Mangrove protest and brought together a wide radical left alliance, including representatives from the IMG, the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League, various radical university societies, as well as individual members of the Communist Party, the Young Communist League, International Socialism, and the Irish Solidarity Campaign.[45]Red Mole, (no issue number) Jan 1-15 Jan 1971, cited in Waters, 2018. Special Branch files on this march commented that the protesters were mainly white (and also that the Black Panther Movement, involved in the organisation, thought that this was a good idea, to show the police that they could not get away with racialism).

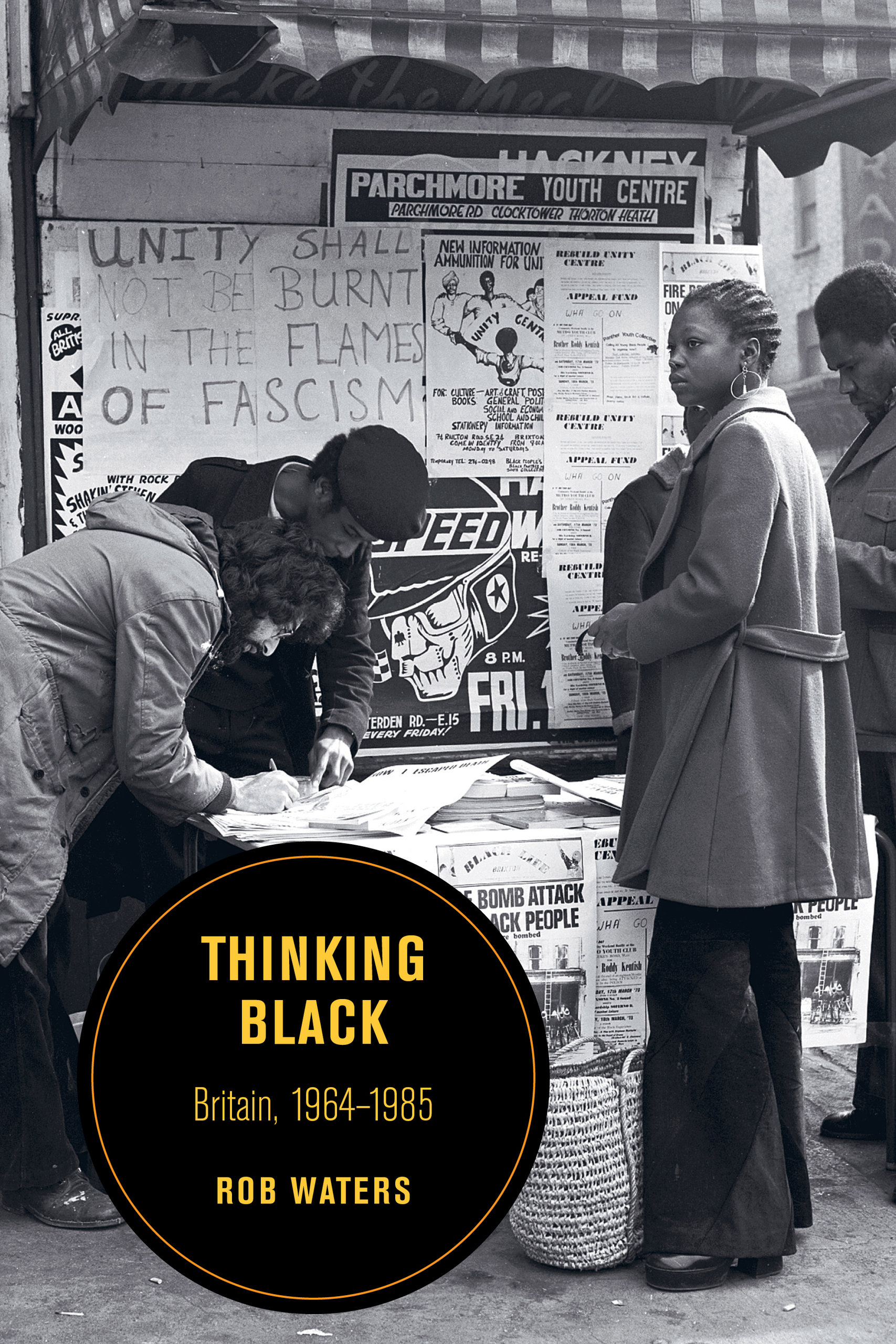

From January 1971, the BDC established a Black Defence and Aid Fund ‘to raise funds to assist black people and organisations faced with mounting legal bills and fines’, targeting ‘ with sympathisers,’ trade unions and political groups for donations.[46]Rob Waters,Thinking Black, 1964-1985, University of California Press, November 2018, pp117-118.

At a campaign later that year against the 1971 Immigration Bill, the platform included Tariq Ali, the Northern Irish civil rights campaigner Bernadette Devlin MP, the anti-apartheid activist Peter Hain, Tony Polan of the International Socialists, and speakers from the Indian Workers’ Association, the Black Panther Movement, and the Black Liberation Front.[47]Black Defence Committee, “Hands Off Black People: Smash the Immigration Bill!” poster for a public meeting at Conway Hall, June 10, 1971, British Library, cited in Waters (2018) pp117-118. According to Rob Waters, ‘The group also worked with black radicals as it grew, with new branches beyond London established on the back of the Black Panther Movement’s speaking tours – a detail that also suggests the commitment the Panthers had to sustaining the alliance. Soon they were campaigning on a raft of cases championed by the black radical press’, mainly focused on police harrasment.[48]Rob Waters,Thinking Black, 1964-1985, University of California Press, November 2018, pp117-118.

For more on the links between the various radical left groups in the late 1960s and early 1970s, see our five-part series: 1968 – Protest and Special Branch.

Material for this article is taken from Rosie Wild, ‘Black was the Colour of Our Fight: Black Power in Britain 1955-1976′, PhD dissertation (2008), except for the final section, which is partly based on Rob Waters, Thinking Black 1964-1985, University of California Press November 2018.

References

| ↑1 | Information taken from the document ‘Names and addresses of financial members of UCPA’, held in Tony Soares’ private collection. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | UCPA, ‘Black Power in Britain: a Special Statement by the Universal Coloured People’s Association’, 10 September 1967. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., p. 4. |

| ↑4 | This followed on from the short-lived Black Power Speaks, which came out monthly between May and July 1968 and was edited by Obi Egbuna. |

| ↑5 | UCPA flyer, February 1967. |

| ↑6 | See undated UCPA flyer, ‘A message to black voters’. |

| ↑7 | UCPA, ‘Black Power in Black Unity, undated leaflet. |

| ↑8, ↑22 | Tony Soares, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 23 August 2004. |

| ↑9 | Lester Lewis, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 14 September 2004. |

| ↑10 | ‘Black Unity and Freedom Party Manifesto’, 26 July 1970. |

| ↑11 | Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 p61 (accessed February 2019). |

| ↑12 | INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑13 | A black worker stands on picket in condemnation of British imperialist atrocities in Ireland, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑14 | Black Workers wholeheartedly support their Irish class brothers and sisters, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑15 | The last time ‘Power to the People’ appeared on a Black Voice masthead was volume 4, number 1, which given the subjects of the articles, one can deduce was published at the start of 1973. See also, ‘The truth about the Spaghetti House Siege’, Black Voice 5:3 (1975), back page. |

| ↑16 | See Metropolitan Police file MEPO 2/11409: ‘Benedict Obi Egbuna, Peter Martin and Gideon Ketueni T. Dolo charged with uttering and writing threats to kill police officers at Hyde Park, W2’, held at the National Archives (NA). |

| ↑17, ↑35 | Linton Kwesi Johnson, interviewed by Rosie Wild, 17 September 2004. |

| ↑18 | See DPP2/4890: ‘Rupert James Frank, Leonard Anderson, Edmund Lecointe and Keith Spencer (Black Panther Movement members) riot and incitement on August 31, 1970 in SE11. Convicted’ at the NA. |

| ↑19 | See MEPO 2/11409, p. 2. |

| ↑20 | See BPM flyer ‘Black People Don’t Vote: organise against exploitation and British institutional racism’, June 1970. |

| ↑21 | Transcript of an unpublished interview with Anne Walmsley on 16 January 1986, p. 4. The transcript is part of the Caribbean Artists Movement papers held at the George Padmore Institute. |

| ↑23, ↑24 | ‘B. L. F. Projects’, Grass Roots 4:1 (1975), p. 15. |

| ↑25 | Undated BLF leaflet from Tony Soares’ private collection. |

| ↑26 | Information from interviews and email correspondence with Tony Soares. |

| ↑27 | See ‘BLF activities’, Grass Roots 3:3 (May 1974), p. 2. Ujima was still in existence in the 21st century. |

| ↑28 | Information on the national distribution of Grass Roots provided by Tony Soares. |

| ↑29 | Most of the information on the Fasimbas in this paragraph comes from former activist Winston Trew’s self-published memoir Black for a Cause (Derbyshire, 2010). pp. 186-7. |

| ↑30 | The 1972 merger of the Fasimba and the BLF is reported in a potted history of the BLF in Grass Roots, 4:4 (January 1976), p. 2. |

| ↑31 | The Tottenham Court Road Two were a pair of Jesuit students from Oxford University accused of mugging tube passengers by Ridgewell and arrested at Tottenham Court Road tube station. |

| ↑32 | Duncan Campbell, How a ‘bent’ policeman could be key to clearing a man’s name, 40 years on, The Guardian, 28/8/2017, accessed 24/2/20. |

| ↑33 | Duncan Campbell, ‘Oval Four’ men jailed in 1972 cleared by court of appeal in London, The Guardian, 5/12/19, accessed 24/2/20. |

| ↑34 | Duncan Campbell, Final Member of the Oval Four has 1972 Conviction Overturned, The Guardian, 24/3/20, accessed 22/5/21. |

| ↑36 | See MEPO 31/4: ‘Malik, MA, alias Michael X, of the Racial Adjustment Action Society: complaints of intimidation, victimisation and harassment by police following a raid on the Society’s headquarters, the “Black House”, 95-101 Holloway Road, N7 on 17 April 1970. Malik and others arrested for robbery and blackmail 1970-1971’, held at the NA. |

| ↑37 | See FCO 63/613: ‘Black Power movement in Caribbean’, held at the NA. |

| ↑38 | Red Mole, Vol.1. No.1 March and No.8, August 1970. |

| ↑39 | Red Mole, Special Election Broadsheet, ca. 1970 |

| ↑40 | ’Donations to A. Williams, 3 Hornsey Rise Gardens N.19′, in Red Mole, Vol. 1, No.6, 1-14 June 1970. It is unclear if and how this fund relates to the Black Defence and Aid Fund to support the Mangrove Nine Trial discussed below. |

| ↑41 | Red Mole, Vol. 1, No.7, July and No.8, August 1970. |

| ↑42 | George Joseph, ‘Trinidad’, Red Mole, 1. 5 (14 May 1970), p. 9 |

| ↑43 | According to Special Branch, when George Joseph was elected treasurer of the UCPA, he was also a member of the International Marxist Group. The Special Branch report cites the membership to make the point that the UCPA seemed to be moving towards a more Trotskyist position after the imprisonment of Tony Soares in February 1969 and the expulsion of Harold Moore, both Maoists. (See the listing for the Universal Coloured People’s Association in Appendix A, “Black Power” Organisations in the United Kingdom’ of the Special Branch report “Black Power” in the United Kingdom, 1970, in HO 325/143, held at the National Archives.) We have not been able to find confirmation of Joseph being a member of the IMG, nor for him being elected as treasurer. While the UCPA was indeed full with ideological rifts, the BUFP co-founded by Joseph from the remains of the UCPA in mid 1970 identified as Maoist – as was pointed out above. (As was mentioned, Joseph was also a member of the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front, a Maoist group.) Though not entirely impossible, the IMG membership in 1969 seems highly unlikely. |

| ↑44 | Red Mole, Vol. 1, No. 11, November 1970) |

| ↑45 | Red Mole, (no issue number) Jan 1-15 Jan 1971, cited in Waters, 2018. |

| ↑46, ↑48 | Rob Waters,Thinking Black, 1964-1985, University of California Press, November 2018, pp117-118. |

| ↑47 | Black Defence Committee, “Hands Off Black People: Smash the Immigration Bill!” poster for a public meeting at Conway Hall, June 10, 1971, British Library, cited in Waters (2018) pp117-118. |