‘lucid examples of oppression against black minorities’

Eveline Lubbers, 12 January 2016

When Nelson Mandela passed away in 2013, British politicians were queueing up to pay tribute. However, it should not be forgotten that the British police went to enormous lengths to infiltrate and disrupt the campaign in this country to help sweep away apartheid. Margaret Thatcher denounced the African National Congress as a typical terrorist organisation.

Previously confidential official files released under the Freedom of Information Act show how Special Branch penetrated the Anti-Apartheid Movement from top to bottom over 25 years – at least from 1969 to 1995. The files presented here come from two different sources. One set was unearthed in 2005 by BBC journalist Martin Rosenbaum, who kindly agreed to share them with the Special Branch Files Project. An additional batch covering 1969-1970 are Special Branch files from the National Archive, photographed by The Guardian journalist Rob Evans. The collection includes files on the policing of the Stop The Seventy Tour (STST) and the protection of the Springboks, the South African Rugby team, touring the UK.

The material Rosenbaum saw suggests that Special Branch had around 30 inch-thick files cataloging its surveillance of the anti-apartheid movement. They contain a mixture of public documents such as leaflets and newspaper cuttings and private information, such as secret reports of demonstrations and meetings. It seems that any demonstration, no matter how small, such as a picket at a local supermarket, was spied upon and registered in the files of Special Branch. In a similarly thorough way, the reports contain minutes of meetings from local branches in the suburbs to invitation-only gatherings where protests were planned and the strategy of the Movement was discussed at the highest level.

Reliable sources

From the files, it is clear that Special Branch had people on the inside at various levels of the movement. The documents contain frequent references to information received from ‘secret and reliable’ sources. Because Special Branch is pretty serious about protecting their sources, it is difficult to say whether the information comes from informants, activists who have been recruited by the police to pass on information, or from infiltrators, police officers gone undercover, living the life of a dedicated activist.

For instance, a ‘secret and reliable source’ supplied information about the monthly meeting of the Highgate branch of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in June 1982. Six campaigners were at the meeting which was held at the home of one of the activists. The source appears to have attended as he or she was in a position to report details of the meeting, such as the fact that it started at 7.30pm and ended at 10.20pm, frustrations about the lack of attention for a South African dispute and the organising of leafleting in local shopping streets the following weekend.

One message in 1981, notes that the public sector union NUPE had decided to picket the South African embassy. Special Branch decided not to pass this on to their colleagues in the Met’s Public Order Branch A8 because it ‘may well come from sensitive source’.

Special Demonstration Squad, the SDS.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement was amongst the first political groups to be penetrated by the Special Demonstration Squad, set up in 1968. The 2002 BBC documentary True Spies interviewed Special Branch officer Wilf Knight, the handler of Mike Ferguson, one of the unit’s first infiltrators. Wilf recalls how Mike targeted the ‘Stop the Tour’ campaign against the visit of the Springboks. There was huge opposition to the planned visits of the rugby and cricket teams who were seen as ambassadors for Apartheid. Demonstrations were held, and there were plans to disrupt the tour. One of the motors behind the campaign was Peter Hain (MP for Neath until the 2015 elections and Foreign Office minister in 2002); Wilf claimed that Mike worked himself up to being Hain’s number two. The latter told True Spies that he could not remember a ‘Mike’ being that close to him. The MP indeed features in a lot of the Special Branch Reports, however, information comes from many different sources as for instance this report about the run-up to the big match in Twickenham in 1970 shows.

Many of the reports on the STST are prepared by DI Gerry Donker, ‘an officer with comprehensive knowledge of South African politics’, according to authors Ray Wilson and Ian Adams in A History of Special Branch (2015). They say Donker’s reports ‘were based on information supplied by a source close to the leadership of the Stop The Seventy Tour Committee, which was supplemented by Special Branch’s coverage of STST’s meetings and rallies and by surveillance.’ However, his reports reveal that Donker also made inquiries himself, for instance into Hain’s background, concluding that although he was the public face of the campaign the ‘real instigator’ was his ‘strong-willed’ mother.

Other reports on the AAM and STST, sometimes co-signed by Donker, are compiled by a DI R Wilson, which most probably is Riby Wilson who also was a desk officer at the time, collating the intelligence brought in by undercover officers and other informers. He was also part of the Special Branch team that investigated the Angry Brigade in the early 1970s. (N.B. this is an update from an ealier version of this article that named Ray Wilson, one of the authors of the 2015 book on Special Branch, as the SDS officer spying on the AAM, Indeed he has also been a member of the SDS in the early days, but it is unclear in which period and what his roles have been.)

Internal files show that for the police intelligence about the leaders of the demonstrations and their plans was crucial to organise the protection of the Springbok rugby tour and the actions of the STST.

Of course, the Anti Apartheid Movement was aware of the risk of infiltration. Marked SECRET, this report shows that despite precautions, spies got in nonetheless:

‘Pathological dislike of the police’

Special Branch regularly received reports of the movement’s members-only annual general meetings, at which the group’s political strategy for the coming year was discussed. The reports give details of those elected to the movement’s executive committee, from the late sixties to the mid eighties the secrect agents dilligently registered whether individuals were linked to the South African or British Communist Party, along with the makes and registration numbers of their cars. It must be said that in 1969 the observation was made that there is a gulf between ‘the British Communist party overtly active in a democracy’ and the South African one ‘operating in a much more intolerant state’ ; comparison between the two make the mechanisms of the British counterpart look like ‘a vicar’s tea party’.

The files also include internal documents, such as this report from 1980 that notes the disappointment about the falling interest of its own members, the lack of co-operation between the various anti-apartheid and liberation movements and by the level of support it is getting from unions.

While some spies seemed impressed by what they heard – with one report of a rally referring to ‘lucid examples of oppression against black minorities’ and ‘compelling’ arguments from ‘a barrage of quality public speakers’ – others clearly found their work rather tedious, as they had to sit through long speeches at boring meetings.

Sometimes quite strong language is used when writing up reports of what was heard:

The smallest meeting and tiniest piece of information

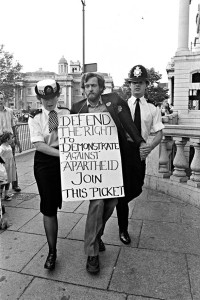

The files contain reports of demonstrations and pickets that include names of speakers, what they said, how they were received by the audience and also methodical listings of the banners carried, leaflets distributed, slogans chanted, organisations represented, while known members of groups were identified and put on file.

It is striking how it seems that no detail is too trivial to be stored.

One report details how the Croydon branch of the Anti-Apartheid Movement held a meeting at 7.30pm on May 27 1982 at the White Horse Manor school in Thornton Heath. How many campaigners were at this meeting? Seven, it seems.

In October 1982, a Home Beat officer in Barnet, north London deemed it necessary to report to the Commander of Special Branch that ‘he had discovered a shed which contains a large number of political posters with a left-wing bias.’

Special Branch noted at one point in the 1970s how a 17-year-old had formed a local group in the west London suburb of Ealing. Even the fact that a copy of the monthly members newsletter has been obtained by ‘a reliable source’ is worth documenting.

Only on very rare occasions would Special Branch acknowledge that there were limits to what they were doing. ‘SB coverage of lobbying at the House of Commons does not normally include coverage of meetings held inside the House itself.’ However, the presence in the Grand Committee Room of several members of the City of London Anti Apartheid Group (CLAAG) could not be left without discreet observation since the group was considered ‘a ‘front’ for the violence prone Trotskyist organization known as the Revolutionary Communist Party’:

Disbanded – but no end to the spying yet

For many years the Anti-Apartheid Movement and alined groups such as was one of the most active protest groups in Britain, until the end of white minority rule in South Africa in the early 1990s. The monitoring of the movement continued until the organisation was disbanded in 1995 following the end of apartheid and succeeded by a group called Action for Southern Africa (ACTSA).

A Special Branch minute noted: ‘ACTSA seems to be a broad-based support group concerned mainly with providing information and education on issues in southern africa; it would appear to be of little interest to this Branch at the present time.’

Peter Hain however recently discovered that his file was not closed at the time. Former undercover officer turned whistleblower Peter Francis revealed that the file still existed during the period from 1990 when he joined Special Branch to when he left the police in 2001, exactly when Hain was an MP. The same was true for nine others, including Ken Livingstone and Jeremy Corbyn. Hain was outraged, saying spying on MPs is a violation of the Wilson doctrine and raises questions about parliamentary sovereignty. Lord Pitchford has since decided to include the spying of MPs in the Inquiry into undercover policing. Hain meanwhile wonders whether the police and the security services ‘really have their eye on the ball’. He warns that ‘conflating serious crime with political dissent unpopular with the state at the time is different. It means travelling down a road that endangers the liberty of us all.’

N.B. Hain was nominated for a life peerage in August 2015 and used the occasion to make a case for radical reform of the House of Lords. In December 2015, he received a top South African award for his years of anti apartheid activities.

Updates

- In May 2017, Peter Hain was accepted by the official Undercover Policing Inquiry as a ‘core participant’ for having been spied on as an anti-apartheid campaigner in the 1960s and 1970s up until 2002 at least, when he was a Member of Parliament (he would move on to be Secretary of State between 2005 – 2008).

- In January 2020, Jonathan Rosenhead, an 81-year-old retired academic started a case to overturn a criminal conviction he received after taking part in an anti-apartheid protest in 1972. He recently discovered that one of the men who was convicted alongside him was an undercover police officer who was pretending to be a leftwing campaigner. The spy called himself Michael Scott and adopted a fake identity to infiltrate three leftwing groups, including the Anti-Apartheid Movement, for five years. Scott’s superiors authorised him to use his fake identity in the criminal trial and to be convicted under his alias. For more detail, see the Undercover Research Group profile on Michael Scott.

-

- Rob Evans, Man, 81, seeks to quash conviction for apartheid protest, The Guardian, 6 January 2020.

- Profile on ‘Michael Scott’, undercover officer, Undercover Research Group, last updated January 2020.

Also see: Anti Apartheid Movement – Files overview.

This story is based on:

- Martin Rosenbaum, Tracking the anti-apartheid groups, BBC Freedom of Information Unit, 27 September 2005, (accessed November 2015).

- The Right to Know, broadcasted on BBC Radio 4 at 2000 BST on 27 September 2005.

- Rob Evans, Documents show how Special Branch infiltrated Anti-Apartheid Movement, The Guardian, 27 September 2005, (accessed November 2015).

- Rob Evans, British police spied on anti-apartheid campaigners for decades, The Guardian, 10 December 2013, (accessed November 2015).

Further reading:

- Solomon Hughes, Apartheid: Protests do work — just ask Thatcher. Government papers from 1984 show how rattled the South Africans and their British allies were over anti-apartheid activism, the Morning Star, 23 May 2014 (accessed December 2015) This article discusses papers released by the Home Office, as yet not in our collection. Special Branch dealt with the public order side of things and the demonstration that the AAM organised at the occasion, or so it seems from the files released to Martin Rosenbaum. See for instance this Special Branch Threat Assessment, 29 May 1984.

- Martin Plaut, What really happened when Margaret Thatcher met South Africa’s P W Botha?, the New Statesman, 3 January 2014 (accessed December 2015)

- Matt Lloyd, Rugby and apartheid: 50 years on from the ‘Battle of Swansea’, BBC News, 15 November 2019 (accessed Jan 2020)

- Gavin Brown, Surveillance of anti-apartheid activists revealed, Non-Stop Against Apartheid, 26 March 2013 (accessed Jan 2020)

- Gavin Brown, PW Botha, police spies, and the South African Embassy Picket Campaign 1984, Non-Stop Against Apartheid, 30 May 2014, (accessed December 2015). Includes the photo below of Jeremy Corbyn arrested for defying the ban on demonstrating in front of the South African Embassy in London.