Dónal O’Driscoll, Undercover Research Group, July 2019

In February 2018, the Undercover Policing Inquiry revealed that Special Demonstration Squad officer ‘HN347’ had, using the alias Alex Sloan, infiltrated the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front in 1971.[1]In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 14 November 2017 (accessed 15 November 2017).[2]Email to core participants, ‘20180208 UPCI to all CPs – HN343 and HN347 cover names’, Undercover Research Group, 8 February 2018, referencing update of the webpage UCPI.org.uk/cover-names. The INLSF was a small Maoist group active in London from 1969 to 1971 and was one of a number of Irish support groups targeted at the time. It organised a number of protests demonstration against the British involvement in Northern Ireland and did work within the London Irish community, before moving on to focus on the selling of its newspaper, the Irish Liberation Press. The driving force in the group was its General Secretary Edward Davoren – whose house acted effectively as its base of operations.[3]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.[4]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).

The following article sets out a history of the group and how it is was targeted. It links different people, police and who they were targeting, not just by undercover work and demonstrates the early adoption of tactics by the Special Demonstration Squad. The second, probably the more significant, is that through the INLSF we have the earliest known interaction of an undercover officer with a family justice campaign, that of Stephen McCarthy, a young man who died in 1969 having been injured during his arrest.

We are grateful to Dr Norman Temple for sharing his memories of the INLSF.[5]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Table of Contents

Edward Davoren

Edward Davoren was a prominent figure in London Maoist circles at the time having been politically active since the 1950s, including being deported from South Africa in 1964 for trade union activities.[6]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). In 1968-1969 he was closely connected to Abhimanyu Manuchanda who ran the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League. The RMLL was behind the British-Vietnam Solidarity Front and active in the Revolutionary Students Socialist Federation (RSSF), taking part in many significant political events at the time.[7]Dónal O’Driscoll, 1968 – Protest and Special Branch, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, 14 April 2018 (accessed 5 February 2019). Both men were named in Special Branch files of late 1968 as significant organisers of protests ahead of the 27 October 1968 Vietnam War demonstration.[8]Weely report on V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). In 1968, Davoren became convenor of the London branch (Secretary of the London Conference) of the RSSF.[9]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).[10]Davoren Defence Fund, The Marxist, no.9, Spring 1969 (accessed via Marxists.org).

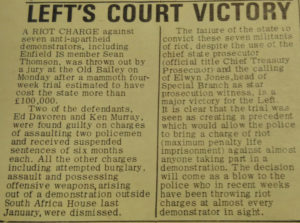

On 12 January 1969, Davoren was one of 31 anti-apartheid protestors arrested at a demonstration at the South African High Commission at Trafalgar Square, London. A contemporary report recounts that he was snatched from the group of protestors, bloodying his face and provoking the crowd in the process.[11]Black and White Unite and Fight!, Freedom News, vol.30, no.2, 18 January 1969. Davoren, then Secretary of the London Conference of the RSSF, was detained in hospital and subsequently remanded to Brixton prison.[12]Davoren Defence Fund, The Marxist, no.9, Spring 1969 (accessed via Marxists.org). Seven of those arrested went to trial, of whom all were acquitted bar Davoren and another who were convicted of assault of two policemen, for which they received suspended sentences. The case was even mentioned in Parliament.[13]Central Criminal Court (Trial), Hansard (Parliament.uk), vol. 793, 19 December 1969.

A file on the arrest and prosecution of Davoren is held in the National Archives and lists several officers from Special Branch as having been present at the protest and who provided witness statements for the prosecution – among them DCI Elwyn Jones, DI Gerrit Donker, Det. Sgt. John Wilson and DC Anthony John Bushell. Jones makes appearances in various police files targeting of left-wing protestors including conducting the September 1968 raids on the offices of the Black Dwarf newspaper.[14]Left’s court victory, Socialist Worker, 20 November 1969.[15]Dónal O’Driscoll, 1968 – Protest and Special Branch part 5: Additional Material, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, 2018 (accessed 5 February 2019). Wilson would become head of Special Branch in the 1970s, and is noted for his role in rebuilding Special Branch’s Irish section.

Documents from this trial are held at the National Archives, of which statements from Special Branch officers can also be found on this site.

In August 1969, Davoren split from Manchanda. Initially he focused on student politics, setting up his own version of the RSSF, but in 1970 he moved onto Irish related politics, establishing the INLSF with himself as the general secretary, while co-founder Joe O’Neill was its chairman. Much of the groups work took place at Davoren’s home in Golders Green, North London.[16]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Activities of the INLSF

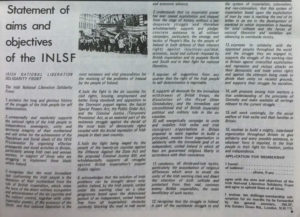

The group was founded in summer 1969, with meetings taking place at The Cock pub in Kilburn. Its formal launch came on 27 September 1969, in a conference at Conway Hall.[17]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).[18]Counter Revolutionaries Get Hammered, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, 1970. Available via Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line (marxists.org), transcription, editing and mark-up by Sam Richards & Paul Saba.

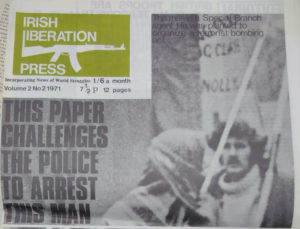

Initially the group organised protests and events, raising awareness on the struggle then taking place in Northern Ireland. This included organising an exhibition on armed struggle in Ireland as a whole. The group also produced a several page leaflet on general rights on being arrested and representing oneself at court.[19]A copy of the leaflet exists in the archives of John Chesterman, held at the London School of Economics library. In March 1970 the group began issuing its newspaper, the Irish Liberation Press.[20]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).

Once the Irish Liberation Press was established as a monthly publication, it became the group’s main focus. Davoren was its editor and wrote most of the articles. Meanwhile, the rest of the group would pair up on Friday nights to go around Irish pubs in London selling it.[21]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

The INLSF was never a particularly large group. Into 1971 it held meetings every Sunday night at the Marquis of Clanricarde pub in Paddington, described as ‘political education classes’.[22]I.N.L.S.F. Activities & services, Irish Liberation Press, No.1, Vol.1, March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). This was an open circle for supporters interested in finding out more and usually attracted 15-18 people. There was also a secret, inner core group of 7-8 people which actually ran things, meeting at Davoren’s flat and generally dominated by him.[23]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Political positions of INLSF

On Ireland

Politically, the INLSF took an anti-imperialist line on Ireland, supporting the Irish Republican Army and Sinn Fein in a qualified fashion.[24]INLSF statement on Sinn Fein and the IRA, Irish Liberation Press, Vol.3, No.1., March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). It saw the cause of the armed struggle in Northern Ireland as a war of national liberation against British colonial aggressors. It used an image of an AK-47 on its paper’s mast-head and, in one intervention of a meeting at which Bernadette Devlin and others were speaking in early 1970, Davoren rose to argue that the gun was the instrument of liberation for the Irish people. However, in 1971, in the wake of internment, the group would argue against the IRA extending their campaign to the British mainland and considered the Provisionals as ‘rightists’.[25]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).

All the same, as there were no groups they felt sufficiently close to in terms of political analysis in Ireland, the INLSF had no particular contacts there.[26]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019. It feuded with the Irish Communist Organisation, another Maoist inspired organisation active in both Britain and Ireland.[27]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).[28]Counter Revolutionaries Get Hammered, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, 1970. Available via Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line (marxists.org), transcription, editing and mark-up by Sam Richards & Paul Saba.

Norman Temple recalls that:[29]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

| The INLSF was an insular group and did not form front organisations with other groups. It was on amicable terms with one black defence organisation based in Finsbury Park and Brixton, but did not do much with them. Davoren also looked favourably at the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist), headed by Reg Birch and based in Camden Town. |

The black defence organisation referenced is likely the Black Panther Movement.[30]The black defence organisation with bases in Finsbury Park and Brixton is likely the Black Panther Movement. The Black Unity and Freedom Party had a base in Finsbury Park, but not Brixton. Communication from Rosie Wild, 9 July 2019.

He also recalled that the INLSF and Birch’s CPB(ML) would have been the two most prominent Maoist groups at that point, with the CPB(ML) focusing more on trade unions.[31]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Black Unity and Freedom Party

The black defence group the INLSF befriend appears to have been the Black Unity and Freedom Party (BUFP), which were mentioned at various occasions in the Irish Liberation Press and which the INLSF would on occasion do joint protests or share platforms with. It was established in summer 1970, Maoist in outlook, and heavily influenced by the Black Panther Party in the USA. It also supported trade union and Irish struggles.[32]42. Independent radical black politics: looking at the BUFP & BLF, WoodSmokeBlog, 25 October 2017 (accessed 5 February 2019).[33]Robin Bunce & Paul Field, Renegade: The Life and Times of Darcus Howe, 2017, Bloomsbury Publishing.[34]Rosalind Eleanor Wild, ‘Black was the colour of our fight’, Black Power in Britain 1955-1976 (PhD thesis), University of Sheffield, August 2008.

The two groups came together under the banner of ‘Anti-Fascist Revolutionary Coordinating Committee of National Minorities’ through which they organised joint protests.[35]A black worker stands on picket in condemnation of British imperialist atrocities in Ireland, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). In July 1971, members of the INLSF came to a conference of the BUFP to present a resolution on Solidarity with the people of Ireland which was ‘wholeheartedly supported’ and ‘adopted unanimously by the many black workers present’.[36]Full text of the resolution: Black Workers wholeheartedly support their Irish class brothers and sisters, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).Furthermore, two figures in the BUFP – including founder George Joseph – were members of the INLSF,[37]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013, p61 (accessed February 2019).[38]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). [39]According to Special Branch, Joseph was also a member of the Trotskyist International Marxist Group when he was elected treasurer of the predecessor of the BUFP, the Universal Coloured People’s Association, probably in 1969. (See the listing for the Universal Coloured People’s Association in Appendix A, “Black Power” Organisations in the United Kingdom’ of the Special Branch report “Black Power” in the United Kingdom in HO 325/143, held at the National Archives). We have not found confirmation for this; though not impossible, membership of a Maoist organisations and a Trotskyist one seems quite unlikely. For more see Black Power – 2. Main groups.

The INLSF also appears to have enjoyed good relations with the Black Panther Movement of Britain, as mentioned above, and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (South Africa), noting various messages of solidarity from these groups in the Irish Liberation Press.

Frank Roche case

In 1969 the British Army began using CS Gas against protests by the nationalist community in Northern Ireland as a supposedly non-lethal alternative to bullets. This was picked up as a campaigning issue by the British left, including the INLSF. In response to the harm being caused by the gas, Frank Roche and Bowes Egan threw CS grenades into the public gallery at the House of Commons on 23 July 1970. Their 1971 trial and jailing became a cause célèbre for British based campaigners around the struggle in Northern Ireland.[40]An appreciation: Butch (Frank) Roche by Rayner O’Connor Lysaght, Irish Republican Marxist History Project (WordPress site), 1 January 2016 (accessed 13 July 2019).[41]Butch Roche from Wexford threw two CS Gas grenades into the House of Commons, Irish Republican Marxist History Project (WordPress site), 29 June 2016 (accessed 13 July 2019).[42]The trial of Frank Roche was covered by a variety of left wing newspapers at the time, including the Black Dwarf. Roche and Devlin would be made Honorary Joint Presidents of the Trotskyst dominated Irish Solidarity Campaign in 1970. See for example, ISC Conference, Red Mole, vol. 1, No. 11, October 1970 (via Marxists.org). Roche’s cause was picked up by the INLSF though Roche was of a different political traditions. Going into 1971 this became a focus for the group.[43]Free the patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971.

Issue 7 of the Irish Liberation Press publishes a letter from Roche to the group (dated 29 October 1970). In it, Roche states he was questioned by Detective Chief Superintendent Ivor Reynolds, the head of ‘C’ Divison at Special Branch[44]C Division or C Desk was the name given to the part of Special Branch which focused on counter subversion and what is now deemed domestic extremism. It looked at all protest and political groups, particularly focusing at the time on the Trotskysts and to lesser degree the Maoists and Irish support groups. It is to them that intelligence gathered by Special Demonstration Squad would have been passed in the first instance. and in particular interrogated about Edward Davoren, even though the two men did not know each other.[45]Letter from Frank Roche, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

The trial of Roche and Egan took place in February 1971. Roche was convicted while Egan was found not guilty. The hearings were picketed by both the INLSF and the Trotskyst based Irish Solidarity Campaign (ISC).[46]Free the patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971.[47]Butch Roche from Wexford threw two CS Gas grenades into the House of Commons, Irish Republican Marxist History Project (WordPress site), 29 June 2016 (accessed 13 July 2019). It was around this time that Special Demonstration Squad undercover, ‘Alex Sloan’, began targeting the group.[48]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

The ISC, which made Bowes Egan joint Honorary President, was itself a target of infiltration by another SDS undercover ‘Alan Nixon’ at that time.[49]Cover Names, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 2019 (accessed 24 July 2019).

Split and the Communist Workers League of Britain

In 1971, Davoren sought to move the group away from purely Irish issues to ones which were British in nature – though they still had a Irish aspect to them.[50]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019. In particular, this included Irish republicans being held in British prisons for which it launch a stickering campaign,[51]Free the Irish Political Prisoners Now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, (Feb) 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). and the Stephen McCarthy justice campaign (see below).

Davoren’s change of focus increased tensions between him and co-founder and chair, Joe O’Neill. The emerging power struggle seemed to have saved Alex Sloan from being fully exposed. For reasons currently unknown, by this time, Davoren and O’Neill had come to the conclusion that Sloan was a police spy. During one of the groups meetings, O’Neill publicly accused him, but when Sloan denied it Davoren did not supported the accusation.[52]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

At the same time, having ambitions to become editor of a British Maoist newspaper, Davoren entered into talks with Birch’s CPB(ML) for a possible merger of the groups, but was turned down. When the existence of these talks became known to the rest of the INLSF, Davoren was viewed by some as trying to sell the group, sparking a split with half the group under Joe O’Neill walking out in June 1971.[53]Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019. The Irish Liberation Press noted that at a special conference of 26 June, three leading members were expelled (including Joe O’Neill), with other leading members from the inner group resigning the following day as the conference continued.[54]Renegades expelled from I.N.L.S.F., Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). The conference appears to have been called to ratify the de facto expulsion of the original three.[55]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).

The INLSF continued to function following the split, producing one further issue of the Irish Liberation Press. However, several weeks later Davoren announced, despite earlier denials, that he wanted to create a British-focused organisation and paper, which those remaining members went along with. Thus in July 1971, the Communist Workers League of Britain (Marxist-Leninists) – CWLB – emerged from what remained of the INLSF.[56]When exactly the Communist Workers League of Britain formed is an open question and source material is unclear. The implication is that it emerged from the split, or that it was the name given to the core inner group of the INLSF. The Irish Liberation Press acknowledged the existence of the CWLB and that it worked with non-members within the INLSF in the article were it reports it’s take on the June 1971 split. See: Renegades expelled from I.N.L.S.F., Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). This and other material (courtesy of of Sam Richards) indicates that it existed prior to then and through-out its existance the INLSF was regarded as a front for the CWLB.

Those remaining with the CWLB / INLSF kept a presence around Irish politics for another six to nine months. At the introduction of internment in Northern Ireland in August 1971, the INLSF held a rally of 600 people on 15th, the march coinciding with the larger International Socialists’ one.[57]Davoren appearing in a report of the protest in The Times, wrongly stated as a speaker with the latter to be with the latter I.S. march. See: Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). Though the INLSF and its paper were never formally abandoned as a project the switch in use of the group’s resources effectively led to the end of activities based around Irish political issues.[58]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

The group kept a presence around Irish politics for another six to nine months. At the introduction of internment in Northern Ireland in August 1971, the INLSF held a rally of 600 people on 15th, the march coinciding with the larger International Socialists’ one[59]Davoren appearing in a report of the protest in The Times, wrongly stated as a speaker with the latter to be with the latter I.S. march. See: Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). Though the INLSF and its paper were never formally abandoned as a project the switch in use of the group’s resources effectively led to the end of activities based around Irish political issues.[60]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

One reason for the changes was that the Irish Liberation Press was seen as a paper for Irish workers in Britain which limited its appeal. It was abandoned as a title in March 1972, when the CWLB replaced it with the publication Voice of the People.[61]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).[62]A new socialist newspaper will go on sale on 1st May, Irish Liberation Press, Vol.3, No.1., March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). The latter would continue to be a target of police attention, with a number of people connected to it being raided by Special Branch in 1973, an IRA bombing campaign being used as the pretext.[63]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). Also communication with Sam Richards who courtesly shared some of their research, 29 July 2019.

Davoren left the group in 1972 and dropped out of active involvement in politics.[64]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).

Stephen McCarthy family justice campaign

Stephen McCarthy was a 19 year son of a North London Irish family. In 1969 he pled guilty to stealing a car and sentenced to borstal, but subsequently escaped. On 16 November 1970, walking with friends in Islington, he was stopped by police and arrested. During this arrest police banged his head against a bus stop to the extent he was taken to hospital – police later said he ran his own head into the bus-stop. Against doctor’s advice, police took him back to Islington Police station to appear before the magistrates court on the 17th, where he was remanded to Wormwood Scrubs prison. On the 14th January 1971 he missed his next court hearing having fallen ill. On being transferred to a specialist hospital on 16th January he underwent an emergency brain operation from which he never regained consciousness. He died on 26th January 1971 and on 19th February, the coroner ruled it was an accidental death.[65]Pigs murder youth, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971.[66]Who Killed Stephen McCarthy – timeline, Felix (newssheet of Imperial College Union), no. 311, 11 May 1972 (via FelixOnline.co.uk). This is a reprint of part of a leaflet titled ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’, issued by the The McCarthy Committee, 50 Courtney Court, Courtney Road, Holloway, N7 7BH.[67]Stephen McCarthy, Hansard (House of Commons Debates), 20 May 1971 – HC Deb 20 May 1971 vol 817 c1507.[68]John Telfair, The police and the death of Stephen McCarthy, Socialist Worker, 17 April 1971.

His parents argued that his death was a result of the police assault at the time of his arrest, and launched a campaign for justice. This was taken up by local MP for Islington East, John Grant, who asked the Home Secretary for a public inquiry.[69]Who Killed Stephen McCarthy – timeline, Felix (newssheet of Imperial College Union), no. 311, 11 May 1972 (via FelixOnline.co.uk). This is a reprint of part of a leaflet titled ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’, issued by the The McCarthy Committee, 50 Courtney Court, Courtney, Road, Holloway, N7 7BH. The family also sought to fund their own inquest and privately prosecute several of the police involved.[70]John Telfair, The police and the death of Stephen McCarthy, Socialist Worker, 17 April 1971.

The INLSF also took up the campaign, working with the McCarthy family.[71]A year of struggle for the INLSF, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). In this, they worked with the BUFP under the RCC banner, including printing a leaflet calling for justice, witnesses and prosecution of the police involved.[72]The people charge police with murder, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). The campaign also gained the support of other north London political groups.[73] On 8/9 October 1971 a joint benefit gig in its name was held, along for the Ian Purdie and Jake Prescott Defence Group (of the Stoke Newington 8). vide infra: ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’ timeline.

On 20 March 1971, the family campaign held a public meeting at Islington Town Hall to mark Stephen’s death and to demand an independent public inquiry. This was followed by a march to the local police station where police attacked the protest. There were 17 arrests among them McCarthy family members and Stephen’s father John was hospitalised.[74]Stephen McCarthy, Class War (paper of the London Alliance in Defence of Workers Rights), no.2, 1972 (accessed via Marxists.org). Also arrested were Edward Davoren and Joe O’Neill, both subsequently convicted of ‘inciting an unlawful assembly and criminal libel of police officers’.[75]Edward DAVOREN and Joseph O’NEILL: convicted of inciting an unlawful assembly and…, National Archives (catalogue of closed record), 1971 (accessed 5 February 2019). Note, it appears to have date of the protest wrong, giving it as 15th March. McCarthy family members were also convicted with Derek McCarthy imprisoned for six months.[76]Who Killed Stephen McCarthy – timeline, Felix (newssheet of Imperial College Union), no. 311, 11 May 1972 (via FelixOnline.co.uk). This is a reprint of part of a leaflet titled ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’, issued by the The McCarthy Committee, 50 Courtney Court, Courtney, Road, Holloway, N7 7BH.[77]McCarthy family fight on against legal lies, Socialist Worker, 24 July 1971. Derek also gives a statement to the Irish Liberation Press, saying only it will print the truth.[78] Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). It seems that the McCarthy family were prevented in some manner from participating in further protests,[79]Police brutality, The Red Mole – special issue on racism, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). though the family continued the campaign into 1972.[80]In memory of Stephen McCarthy, The Red Mole, vol.3, n.35, 24 Jan 1972 (accessed via Marxists.org).[81]Who Killed Stephen McCarthy – timeline, Felix (newssheet of Imperial College Union), no. 311, 11 May 1972 (via FelixOnline.co.uk). This is a reprint of part of a leaflet titled ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’, issued by the The McCarthy Committee, 50 Courtney Court, Courtney, Road, Holloway, N7 7BH. with a protest march taking place on 28 January 1972.[82]Family and supporters of 20-year-old Stephen McCarthy march on the second anniversary of his death in protest at alleged police brutality during his arrest in Upper Street, Islington, London after which he died in police custody, ReportDigital.co.uk (image of demonstration), 28 January 1972 (accessed 5 February 2019). Norman Temple’s recollection is that Alex Sloan may have attended the protest of 20 March.[83]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

The Stephen McCarthy case is, at the time of writing, believed to be the first family justice campaign spied upon by the Special Demonstration Squad. Along with the case of David Oluwale, a black man murdered by Leeds Police also in 1970, these were among the first campaigns to bring attention to the abuse of the coroner system to cover up police brutality, and of suspicious deaths in custody in general.[84]Clive Bloom, Violent London: 2000 Years of Riots, Rebels and Revolts, Springer, 2010.[85]Tim Newburn & Stephanie Hayman, Policing, Surveillance and Social Control, Routledge, 2012.[86]Melissa Benn & Ken Worpole, Death in the City, Canary Press, 1986.

Infiltration of the INLSF

Norman Temple believes that its focus on Irish issues was a significant motivation to infiltrate the INLSF. Even though it was not particularly active with Irish political groups, being in the group would still have allowed the undercover officer to identify who was working with who. Police would have been interested to see if there was a hidden agenda such as fundraising for Irish militants or contacts with the IRA factions, particularly in London.[87]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

The fact that the INLSF had links to radical black power organisations, a key target of Special Branch at the time, may have also played a role in the targeting of the group.[88]In 1967, the state began monitoring black power and liberation in earnest, including creating a ‘Black Power Desk’ to monitor radical black power and liberation groups. See Paul Field, The Real Guerillas, Jacobin Magazine, 14 April 2017; Peter Brook, When cops raided a hip 1970s London cafe, Britian’s Black Power movement rose up, Medium (Timeline.com), 5 Feb 2018; WoodSmokeBlog, 42. Independent radical black politics: looking at the BUFP & BLF, WoodSmokeBlog.wordpress.com, 25 October 2017; Coming soon: Revisiting the question of Special Branch and Black Power, BlackForACause.co.uk – all accessed 24 July 2019.

Alex Sloan

Temple recalls Alex Sloan as someone with a strong Scottish accent, who had no real politics. He was not a prominent person in the group and did not become part of it’s inner circle. He was mainly involved in the selling of the Irish Liberation Press which was the main focus of group activity when he joined. Though its members attended other demonstrations, the group was not organising its own protests at the time.[89]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Prior to the split within the INLSF in May 1971, it was discovered that Sloan was a police spy, though it is not known how this came about. At one of the group’s meeting (see above), Sloan was directly challenged by Joe O’Neill, but saw it off being supported by Davoren. Nevertheless, after the split Sloan resigned from the group, saying he could not trust them any more following the accusation.[90]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

According to Norman Temple:[91]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

| After he had been exposed he did not simply disappear. Instead prior to disappearing, he tried to throw a spanner in the works. There had been a split in the INLSF. He told us that he saw two people outside his flat obviously watching him. One was a person who stayed with the INLSF and the other was a person who had resigned. This was an obvious attempt to make us question the loyalty of one of our members. |

Sloan is not known to have had sexual relations.[92]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Dick Jackson

Contemporary reports in the Irish Liberation Press point to another undercover having been discovered in the INLSF, whose exposure predates the arrival of Sloan. This person was known as Dick Jackson and in Norman Temple’s recollection close to fifty years later, Jackson was uncovered around the time the group became involved in supporting the McCarthy family, and had left before Sloan made his appearance.[93]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Jackson had been a member since before August 1970 (when Norman Temple had joined). Temple recalled him as being ‘one of the guys’, and quite chatty, showing interest in Temple’s other political activities at the time. Jackson had no known sexual relations.[94]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

Having become under suspicion, Jackson’s flat was checked out and it was noted that his books were not the type to be expected of a committed Marxist-Leninist of the time. He was also noted for having a camera, though not uncommon, he did bring it along a lot.[95]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

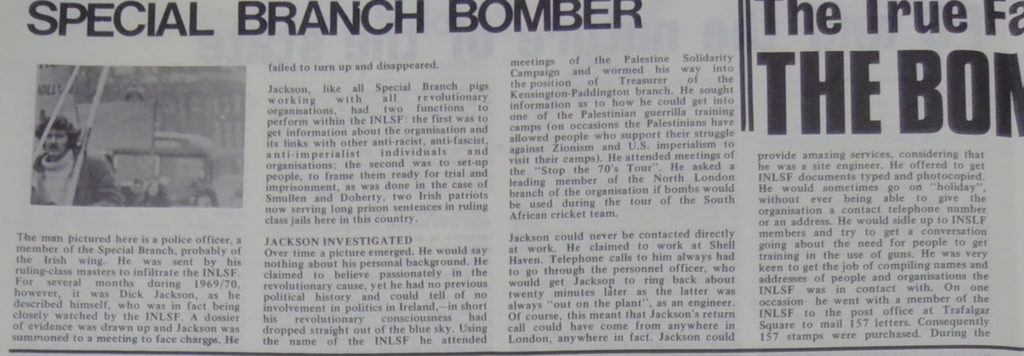

The INLSF revealed their suspicions in their paper in late 1970 and subsequently published a detailed write-up in March 1971. According to this account, Jackson had been with the group for several months over 1969/70, and come under suspicions. When summoned to a meeting to face charges, he failed to turn up and disappeared from the group. The article states:[96]Hunt down this policeman bomber, Irish Liberation Press, Vol.3, No.1., March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org).

| JACKSON INVESTIGATED

Over time a picture emerged. He would say nothing about his personal background. He claimed to believe passionately in the revolutionary cause, yet had no previous political history and could tell of no involvement in politics in Ireland – in short his revolutionary consciousness had dropped straight out of the blue sky. Using the name of the INLSF he attended meetings of the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign and wormed his way into the position of Treasurer of the Kensington-Paddington branch. He sought information as to how he could get into one of the Palestinian guerrilla training camps… He attended meetings of the “Stop the 70’s Tour”. He asked a leading member of the North London branch of the organisation if bombs would be used during the tour of the South African cricket team. Jackson could never be contacted directly at work. He claimed to work at Shell Haven. Telephone calls to him always had to go through the personnel officer, who would get Jackson to ring back about twenty minutes later as the latter was always “out on the plant”, as an engineer. Of course, this meant that Jackson’s return call could have come from anywhere in London, anywhere in fact. Jackson could provide amazing services, considering that he was a site engineer. He offered to get INLSF documents typed and photocopied. he would sometimes go on “holiday”. without ever being able to give the organisation a contact telephone number or an address. He would sidle up to INLSF members and try to get a conversation going about the need for people to get training in the use of guns. He was very keen to get the job of compiling names and addresses of people and organisations the INLSF was in contact with. On one occasion he went with a member of the INLSF to the post office at Trafalgar Square to mail 157 letters. Consequently 157 stamps were purchased. During the stamping Jackson made an excuse to move out of sight down the counter, out of sight. At the end of the stamping four stamps were still left. Jackson often asked about contacts within Ireland. Four of the 157 letters of the mailing were to people in Ireland. He had stolen four letters while out of sight, forgetting that this would leave four stamps over at the end. One afternoon Jackson was caught going through the diary of the general secretary of the INLSF. The diary had been left as bait for Jackson. Jackson possessed an expensive camera which he used to photograph people on demonstrations. He said the prints would be good for the “Irish Liberation Press”. However, the prints rarely ever got back to his paper and it can be safely assumed that they were destined for the files of a very different organisation. The camera, which had been borrowed by the INLSF prior to the point at which Jackson was to be charged, was retained after his disappearance. It has since been stolen from the INLSF office, the organisation believes, by the police. Jackson had stated clearly that there was no telephone where he lived. He had to do this, of course, because if he admitted the existence of the phone it would have been much too easy a matter for the organisation to be able to follow his movements closely. In fact he used to display mock anger at the G.P.O. for taking too long to install a phone, a phone which in fact already existed. Jackson made a slip-up. He told a member of the “Stop the 70’s Tour” to ring him at home over some matter. The person rang Jackson at his home number and when he couldn’t get through, because Jackson was not there at the time, the person rang the INLSF office to try to contact him. INLSF comrades in the office at the time obtained Jackson’s number and rang it later in the day. Jackson picked up and answered the phone. Jackson had a phone alright – 458 1007. But there was one most serious piece of work Jackson tried to get the INLSF to undertake. In the autumn of 1969 he tried to get the INLSF to carry out an act of terrorism. For weeks Jackson had been saying that the organisation must do something more than organise rallies, demonstrations and political education classes. Jackson proposed that a bombing be organised. It was explained to him that the job of the INLSF was to educate and mobilise the masses for a revolutionary struggle, and that this was quite different from engaging in acts of individual terrorism. Political power, it was explained, grows out of the barrel of a gun, but it is the masses led by the working class who must grasp this truth in theory and apply it in practice. Jackson (or rather his masters) chose to make his proposal at precisely the time that the INLSF general secretary [Davoren] was on £1,500 bail awaiting trial at the Old Bailey on charges stemming from an anti-fascist demonstration which had taken place earlier in the year at South Africa House. When Jackson realised that his game was up and that he was to be charged in front of the INLSF, he disappeared. |

The Undercover Policing Inquiry has not released the name of any undercover by this name at the time of writing (July 2019). However, it is of note that there was an undercover ‘Dick Epps’ (HN336) who is said to have infiltrated the International Marxist Group, Vietnam Solidarity Campaign and British Communist Party 1969 to 1972.[97]Sir John Mitting, In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 14 November 2017 (accessed 15 November 2017). Though there is no concrete evidence that Jackson was an officer of the Special Demonstration Squad, the activities set out by the Irish Liberation Press article show a strong overlap with known methodology of undercovers from the SDS.[98]See, for example, Peter Salmon & Eveline Lubbers, The Fifteen Questions we work with, Undercover Research Group, 2 November 2015. However, beyond the newspaper report, additional corroboration is required to be 100% certain. If it is the case that Jackson was a Special Branch asset in some form or other then his activities raise questions of the degree to which he was an agent provocateur.

Timeline of INLSF

This is an incomplete list of INLSF activities for 1969-1971, mostly taken from its newspaper.

- 27 September 1969: 1st Annual Conference of the INLSF, Conway Hall, London.[99]Statement of Aims, Irish Liberation Press, March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org).[100]A year of struggle for the INLSF, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

1970

- March 1970: first issue of the Irish Liberation Press.[101]A number of issues of the Irish Liberation Press are online at Marxists.org. Others are available at the Linenhall Library archives on the struggle in Northern Ireland, while we have located one or two others in personal archives deposited in various universities.

- March 1970: by this point the Central London branch of the group was having weekly Sunday meetings, described as political education classes. They were open to all supporters and held at the Marquis of Clanricarde pub, Southwick Street, nr. Paddington[102]I.N.L.S.F. Activities & services, Irish Liberation Press, No.1, Vol.1, March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). These Sunday weekly meetings at the same venue continued into 1971.[103]INLSF Political Education, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).[104]Political Education Classes, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). By February 1971 these would also include monthly film-showings.[105]Political Education Classes, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, (Feb) 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 15 March 1970: INLSF organise a demonstration on Irish issues, with a march from Trafalgar Square to Downing Street, the Ulster Office and Irish Embassy.[106] March 15th Irish demo and rally, The Red Mole, vol.1, no.1, 17 March 1970.[107]Events, The Black Dwarf, vol.14, no.30, 7 March 1970. This march receives a statements of support from the Black Panther Movement and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania.[108]The Black Panther Movement statement is published in I.N.L.S.F. Mass Work Among British Working Class, Irish Liberation Press, 1970, vol.1, no.? (CS Gas issue, via Linenhall Library archives)., while that of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania is published in Pan African Congress of Azania (S.African) hails Irish People’s struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.1, March 1970 (via Marxists.org).

- 29-30 March 1970: organised the exhibition: ‘History of Irish Revolutionary Warfare 1708-1970’, held at the Camden Studios, 61 Camden Road, London.[109]Events, The Black Dwarf, vol.14, no.31, 23 March 1970.

- 3 May 1970: INLSF take part in 2000 strong march through London to protest racism against the Pakistani community, at which Davoren speaks. The march is also supported by the Black People’s Alliance and Black Panther Movement.[110]Stephen Ashe, Satnam Virdee, & Laurence Brown, Striking back against racist violence in the East End of London, 1968–1970, Race & Class vol. 58, 24 June 2016.

- 26 July 1970: INLSF members attend conference of the Black Unity and Freedom Party.[111]Black workers wholeheartedly support their Irish class brothers and sisters, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- September 1970: second annual conference held.[112]A year of progress for the INLSF, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 20 September 1970: INLSF hold protest at Hyde Park, attracting 350 people as part of “Solidarity With People of Ireland” Week. During the demonstration, Davoren is given a police summons for hanging too many banners at a protest two months previously. The week includes a repeat showing of their exhibition on revolutionary struggle in Ireland while a planned film showing at Anson Hall, Cricklewood is cancelled by Brent Council at the last minute.[113]”Solidarity With People of Ireland” Week, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, (Oct) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- 26 October 1970: 1st Annual Conference of INLSF, Conway Hall. Joe O’Neill as Chairman, Ed Davoren as General Secretary. As part of a report back on activities, it also notes that it had been organising meetings in Kilburn as well as its weekly poliitcal education / discussion meetings, and the presence of Special Branch officers at its meetings.[114]Report of first Annual Conference, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, (Oct) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- 27 October 1970: demonstration in Hyde Park, speakers for which included Edward Davoren, George Joseph (BUFP), Ghath Armanazi (editor, Free Palestine) & Norman Temple (of Revolutionary Jewish Alliance). Noted that Special Branch were present, filming at it.

- 22 November 1970: picket of US Embassy over the treatment of Palestinians in Israel.[115]”Solidarity With People of Ireland” Week, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, (Oct) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- 8 November 1970: Revolutionary Co-ordinating Committee [RCC] established in meeting between INLSF and the Black Unity and Freedom Party. First formal meeting of the RCC held on 17 November.[116]Editorial, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- November 1970: Issue 7 of the Irish Liberation Press publishes a letter from jailed activist James A “Frank” Roche, sent on 29 October.[117]Letter from Frank Roche, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). The same issue also notes that the INLSF was singled out for criticism by MP John Briggs Davidson; while two INLSF members were just back from Ireland where they had gone to sell the Irish Liberation Press.[118]Fascist MP Attacks I.N.L.S.F., Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- Early December 1970: Joint meeting between INLSF and the Kensington & Paddington Branch of the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign took place, discussing ‘the similarities in the struggles of the Palestinian and Irish people and the need to build a principled anti-imperialists solidarity movement in Britain’.[119]INLSF Solidarity with Palestine People, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 13 December 1970: first RCC demonstration to be held at Speakers Corner with march to Downing Street and the US Embassy to protest US bombing of Vietnam.[120]Irish Liberation Press;, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- 14 December 1970: start of trial three INLSF members for having disrupted a general election meeting being addressed by Barbara Castle in Liverpool; all three, including Joe O’Neill, convicted.[121]INLSF Officers “Guilty”, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). The General Election was held in June 1970[122]Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- December 1970: two INLSF paper sellers arrested at the Gresham Ballroom, Archway.[123]Ruling Class Attacks Against INLSF Escalate, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

INLSF banner passing Houses of Parliament, circa. 1970/1971. - 8 December 1970: INLSF through the Revolutionary Co-ordinating Committee [RCC], do a stall at the mobilisation against the Industrial Relations Bill; it also set up its own platform at Speaker’s Corner on the day, and took part in the large march on which it brought a sound-system to play the Internationale.[124]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 13 December 1970: RCC hold rally at Speakers Corner, Hyde Park against resumption of bombing of North Vietnam, followed by march to US and Irish Embassies and Downing Street; the day ended with an RCC organised film showing.[125]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 13 December 1970: INLSF, supported by BUFP, organise a protest at the Irish Embassy over the Irish Government’s plan to introduce internment[126]No Internments!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). (announced 4 December 1970[127]Brian Hanley, ‘A step on the road to dictatorship’: The threat of internment during the Troubles, ”Irish Times”, 13 October 2018 (accessed 5 February 2019).).

- 20 December 1970: INLSF activists join protest at Spanish Embassy in support of the Basque peoples struggle.[128]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 28 December 1970: INLSF mobilise for a protest at Spanish Embassy called in support of Basque activists sentenced to death in Spain.[129]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

1971

- 9/10th January 1971: INLSF activists travel to various British cities to sell the Irish Liberation Press.[130]INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- January 1971: Davoren addresses a large public meeting of the BUFP held on 17th January in Deptford on police brutality, which is followed by a march to Ladywell police station. This was in the wake of several BUFP members being assaulted by police on 10 January, and a separate incident were fascists petrol-bombed a black house party on Sunderland Road, the INLSF supporting the BUFP’s campaigning around these. Further BUFP / INLSF public meetings were held on New Cross (13 Jan) & Hackney (31 Jan). The INLSF also announce its intention to attend the picket of the court on 25 February when the BUFP activists were due to stand trial.[131]Black workers wage struggle against police brutality, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971.

- 8 February 1971: INLSF hold a picket at the Old Bailey for the opening of trial of Frank Roche and Bowes Egan who had been arrested having released tear gas into House of Commons in protest over its use in Northern Ireland. The Irish Solidarity Campaign also holds their own protest.[132]Free the patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971.

- 13 February 1971: INLSF call press conference about recent bombings in Britain, and also to release details of Dick Jackson as a Special Branch agent.[133]Press Conference, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- ca. February/March 1971: police detain INLSF paper sellers.[134]News briefs (page 21), Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- Easter (April) 1971: a car of INLSF activists travel to Ireland, and sell their newspapers. They visit Dublin, Belfast, Derry and Cork.

- Easter 1971: start of stickering campaign to raise awareness of the issue of Irish republicans in British jails.[135]Free these patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).

- 11 & 12 April 1971 INLSF Easter Weekend Programme: On Sunday 11 April, INLSF repeat photo exhibition on Irish Revolutionary Struggle at the Camden Studios, followed by a meeting on politics of James Connolly. On Easter Monday, 12 April, rally and demonstration, meeting at Speaker’s Corner with march to 10 Downing Street, Ulster Office and the Irish Embassy, to be followed by a social in the Spotted Dog pub, High Street, Willesden.[136]Important Announcement: INLSF Easter Weekend Programme, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org).[137]Free the patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971.

- May 1971: split in group over changing emphasis of its political activity, with half leaving as a result. A number subsequently turn to Irish republican politics.[138]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

- July 1971: Communist Workers League of Britain forms.[139]Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019.

- 20 July 1971: INLSF members present at BUFP Conference.[140] Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- 25 July 1971, Davoren of the INLSF speaks on the platform of a demonstration called by the Black Unity and Freedom Party.[141]Molehills – An attempt at disruption, The Red Mole, vol.2, no.14, 14 August 1971.

- 15 August 1971: Anti-internment rally organised by INLSF attended by 600 people, converging with a larger one organised by Trotskyist groups.[142]Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019).[143] Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives).

- March 1972: Irish Liberation Press re-branded as Voice of the People.

Resources

The Encyclopedia for Anti-Revisionism Online (EROL / Marxists.org) host a number of articles which discuss the activities of the INLSF, as well as providing scanned copies of an number of issues of the Irish Liberation Press.

Police statements relating to the 1969 prosecution of Edward Davoren and others can be found on SpecialBranchFiles.uk.

References

| ↑1 | In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 14 November 2017 (accessed 15 November 2017). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Email to core participants, ‘20180208 UPCI to all CPs – HN343 and HN347 cover names’, Undercover Research Group, 8 February 2018, referencing update of the webpage UCPI.org.uk/cover-names. |

| ↑3, ↑5, ↑16, ↑21, ↑23, ↑26, ↑29, ↑31, ↑48, ↑50, ↑52, ↑53 | Undercover Research Group: interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019. |

| ↑4, ↑6, ↑9, ↑17, ↑20, ↑25, ↑55, ↑61, ↑64, ↑142 | Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). |

| ↑7 | Dónal O’Driscoll, 1968 – Protest and Special Branch, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, 14 April 2018 (accessed 5 February 2019). |

| ↑8 | Weely report on V.S.C. “Autumn Offensive”, Metropolitan Police Special Branch, 16 October 1968 (accessed via SpecialBranchFiles.uk). |

| ↑10, ↑12 | Davoren Defence Fund, The Marxist, no.9, Spring 1969 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑11 | Black and White Unite and Fight!, Freedom News, vol.30, no.2, 18 January 1969. |

| ↑13 | Central Criminal Court (Trial), Hansard (Parliament.uk), vol. 793, 19 December 1969. |

| ↑14 | Left’s court victory, Socialist Worker, 20 November 1969. |

| ↑15 | Dónal O’Driscoll, 1968 – Protest and Special Branch part 5: Additional Material, SpecialBranchFiles.uk, 2018 (accessed 5 February 2019). |

| ↑18, ↑28 | Counter Revolutionaries Get Hammered, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, 1970. Available via Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line (marxists.org), transcription, editing and mark-up by Sam Richards & Paul Saba. |

| ↑19 | A copy of the leaflet exists in the archives of John Chesterman, held at the London School of Economics library. |

| ↑22, ↑102 | I.N.L.S.F. Activities & services, Irish Liberation Press, No.1, Vol.1, March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑24 | INLSF statement on Sinn Fein and the IRA, Irish Liberation Press, Vol.3, No.1., March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑27, ↑38, ↑124, ↑125, ↑128, ↑129, ↑130 | INLSF Intensifies Struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑30 | The black defence organisation with bases in Finsbury Park and Brixton is likely the Black Panther Movement. The Black Unity and Freedom Party had a base in Finsbury Park, but not Brixton. Communication from Rosie Wild, 9 July 2019. |

| ↑32 | 42. Independent radical black politics: looking at the BUFP & BLF, WoodSmokeBlog, 25 October 2017 (accessed 5 February 2019). |

| ↑33 | Robin Bunce & Paul Field, Renegade: The Life and Times of Darcus Howe, 2017, Bloomsbury Publishing. |

| ↑34 | Rosalind Eleanor Wild, ‘Black was the colour of our fight’, Black Power in Britain 1955-1976 (PhD thesis), University of Sheffield, August 2008. |

| ↑35 | A black worker stands on picket in condemnation of British imperialist atrocities in Ireland, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑36 | Full text of the resolution: Black Workers wholeheartedly support their Irish class brothers and sisters, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑37 | Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013, p61 (accessed February 2019). |

| ↑39 | According to Special Branch, Joseph was also a member of the Trotskyist International Marxist Group when he was elected treasurer of the predecessor of the BUFP, the Universal Coloured People’s Association, probably in 1969. (See the listing for the Universal Coloured People’s Association in Appendix A, “Black Power” Organisations in the United Kingdom’ of the Special Branch report “Black Power” in the United Kingdom in HO 325/143, held at the National Archives). We have not found confirmation for this; though not impossible, membership of a Maoist organisations and a Trotskyist one seems quite unlikely. For more see Black Power – 2. Main groups. |

| ↑40 | An appreciation: Butch (Frank) Roche by Rayner O’Connor Lysaght, Irish Republican Marxist History Project (WordPress site), 1 January 2016 (accessed 13 July 2019). |

| ↑41, ↑47 | Butch Roche from Wexford threw two CS Gas grenades into the House of Commons, Irish Republican Marxist History Project (WordPress site), 29 June 2016 (accessed 13 July 2019). |

| ↑42 | The trial of Frank Roche was covered by a variety of left wing newspapers at the time, including the Black Dwarf. Roche and Devlin would be made Honorary Joint Presidents of the Trotskyst dominated Irish Solidarity Campaign in 1970. See for example, ISC Conference, Red Mole, vol. 1, No. 11, October 1970 (via Marxists.org). |

| ↑43, ↑46, ↑132, ↑137 | Free the patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971. |

| ↑44 | C Division or C Desk was the name given to the part of Special Branch which focused on counter subversion and what is now deemed domestic extremism. It looked at all protest and political groups, particularly focusing at the time on the Trotskysts and to lesser degree the Maoists and Irish support groups. It is to them that intelligence gathered by Special Demonstration Squad would have been passed in the first instance. |

| ↑45, ↑117 | Letter from Frank Roche, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑49 | Cover Names, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 2019 (accessed 24 July 2019). |

| ↑51 | Free the Irish Political Prisoners Now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, (Feb) 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑54 | Renegades expelled from I.N.L.S.F., Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑56 | When exactly the Communist Workers League of Britain formed is an open question and source material is unclear. The implication is that it emerged from the split, or that it was the name given to the core inner group of the INLSF. The Irish Liberation Press acknowledged the existence of the CWLB and that it worked with non-members within the INLSF in the article were it reports it’s take on the June 1971 split. See: Renegades expelled from I.N.L.S.F., Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). This and other material (courtesy of of Sam Richards) indicates that it existed prior to then and through-out its existance the INLSF was regarded as a front for the CWLB. |

| ↑57, ↑59 | Davoren appearing in a report of the protest in The Times, wrongly stated as a speaker with the latter to be with the latter I.S. march. See: Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). |

| ↑58, ↑60, ↑83, ↑87, ↑89, ↑90, ↑91, ↑92, ↑93, ↑94, ↑95, ↑138, ↑139 | Undercover Research Group: an interview with Dr. Norman Temple, 19 November 2019. |

| ↑62 | A new socialist newspaper will go on sale on 1st May, Irish Liberation Press, Vol.3, No.1., March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑63 | Sam Richards, The Rise & Fall of Maoism: the English Experience, Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism Online, 2013 (accessed February 2019). Also communication with Sam Richards who courtesly shared some of their research, 29 July 2019. |

| ↑65 | Pigs murder youth, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971. |

| ↑66 | Who Killed Stephen McCarthy – timeline, Felix (newssheet of Imperial College Union), no. 311, 11 May 1972 (via FelixOnline.co.uk). This is a reprint of part of a leaflet titled ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’, issued by the The McCarthy Committee, 50 Courtney Court, Courtney Road, Holloway, N7 7BH. |

| ↑67 | Stephen McCarthy, Hansard (House of Commons Debates), 20 May 1971 – HC Deb 20 May 1971 vol 817 c1507. |

| ↑68, ↑70 | John Telfair, The police and the death of Stephen McCarthy, Socialist Worker, 17 April 1971. |

| ↑69, ↑76, ↑81 | Who Killed Stephen McCarthy – timeline, Felix (newssheet of Imperial College Union), no. 311, 11 May 1972 (via FelixOnline.co.uk). This is a reprint of part of a leaflet titled ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’, issued by the The McCarthy Committee, 50 Courtney Court, Courtney, Road, Holloway, N7 7BH. |

| ↑71, ↑100 | A year of struggle for the INLSF, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑72 | The people charge police with murder, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑73 | On 8/9 October 1971 a joint benefit gig in its name was held, along for the Ian Purdie and Jake Prescott Defence Group (of the Stoke Newington 8). vide infra: ‘Who Killed Stephen McCarthy’ timeline. |

| ↑74 | Stephen McCarthy, Class War (paper of the London Alliance in Defence of Workers Rights), no.2, 1972 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑75 | Edward DAVOREN and Joseph O’NEILL: convicted of inciting an unlawful assembly and…, National Archives (catalogue of closed record), 1971 (accessed 5 February 2019). Note, it appears to have date of the protest wrong, giving it as 15th March. |

| ↑77 | McCarthy family fight on against legal lies, Socialist Worker, 24 July 1971. |

| ↑78, ↑143 | Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.5, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑79 | Police brutality, The Red Mole – special issue on racism, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑80 | In memory of Stephen McCarthy, The Red Mole, vol.3, n.35, 24 Jan 1972 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑82 | Family and supporters of 20-year-old Stephen McCarthy march on the second anniversary of his death in protest at alleged police brutality during his arrest in Upper Street, Islington, London after which he died in police custody, ReportDigital.co.uk (image of demonstration), 28 January 1972 (accessed 5 February 2019). |

| ↑84 | Clive Bloom, Violent London: 2000 Years of Riots, Rebels and Revolts, Springer, 2010. |

| ↑85 | Tim Newburn & Stephanie Hayman, Policing, Surveillance and Social Control, Routledge, 2012. |

| ↑86 | Melissa Benn & Ken Worpole, Death in the City, Canary Press, 1986. |

| ↑88 | In 1967, the state began monitoring black power and liberation in earnest, including creating a ‘Black Power Desk’ to monitor radical black power and liberation groups. See Paul Field, The Real Guerillas, Jacobin Magazine, 14 April 2017; Peter Brook, When cops raided a hip 1970s London cafe, Britian’s Black Power movement rose up, Medium (Timeline.com), 5 Feb 2018; WoodSmokeBlog, 42. Independent radical black politics: looking at the BUFP & BLF, WoodSmokeBlog.wordpress.com, 25 October 2017; Coming soon: Revisiting the question of Special Branch and Black Power, BlackForACause.co.uk – all accessed 24 July 2019. |

| ↑96 | Hunt down this policeman bomber, Irish Liberation Press, Vol.3, No.1., March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑97 | Sir John Mitting, In the matter of section 19 (3) of the Inquiries Act 2005 Applications for restriction orders in respect of the real and cover names of officers of the Special Operations Squad and the Special Demonstrations Squad ‘Minded to’ note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry, 14 November 2017 (accessed 15 November 2017) |

| ↑98 | See, for example, Peter Salmon & Eveline Lubbers, The Fifteen Questions we work with, Undercover Research Group, 2 November 2015. |

| ↑99 | Statement of Aims, Irish Liberation Press, March 1970 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑101 | A number of issues of the Irish Liberation Press are online at Marxists.org. Others are available at the Linenhall Library archives on the struggle in Northern Ireland, while we have located one or two others in personal archives deposited in various universities. |

| ↑103 | INLSF Political Education, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑104 | Political Education Classes, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑105 | Political Education Classes, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, (Feb) 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑106 | March 15th Irish demo and rally, The Red Mole, vol.1, no.1, 17 March 1970. |

| ↑107 | Events, The Black Dwarf, vol.14, no.30, 7 March 1970. |

| ↑108 | The Black Panther Movement statement is published in I.N.L.S.F. Mass Work Among British Working Class, Irish Liberation Press, 1970, vol.1, no.? (CS Gas issue, via Linenhall Library archives)., while that of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania is published in Pan African Congress of Azania (S.African) hails Irish People’s struggle, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.1, March 1970 (via Marxists.org). |

| ↑109 | Events, The Black Dwarf, vol.14, no.31, 23 March 1970. |

| ↑110 | Stephen Ashe, Satnam Virdee, & Laurence Brown, Striking back against racist violence in the East End of London, 1968–1970, Race & Class vol. 58, 24 June 2016. |

| ↑111 | Black workers wholeheartedly support their Irish class brothers and sisters, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑112 | A year of progress for the INLSF, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑113, ↑115 | ”Solidarity With People of Ireland” Week, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, (Oct) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑114 | Report of first Annual Conference, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.6, (Oct) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑116 | Editorial, Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑118 | Fascist MP Attacks I.N.L.S.F., Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑119 | INLSF Solidarity with Palestine People, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑120 | Irish Liberation Press;, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑121 | INLSF Officers “Guilty”, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). The General Election was held in June 1970 |

| ↑122 | Irish Liberation Press, vol.1, no.7, (Nov) 1970 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑123 | Ruling Class Attacks Against INLSF Escalate, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑126 | No Internments!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.1, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑127 | Brian Hanley, ‘A step on the road to dictatorship’: The threat of internment during the Troubles, ”Irish Times”, 13 October 2018 (accessed 5 February 2019). |

| ↑131 | Black workers wage struggle against police brutality, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.2, 1971. |

| ↑133 | Press Conference, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑134 | News briefs (page 21), Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑135 | Free these patriots now!, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑136 | Important Announcement: INLSF Easter Weekend Programme, Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (accessed via Marxists.org). |

| ↑140 | Irish Liberation Press, vol.2, no.3, 1971 (via Linenhall Library archives). |

| ↑141 | Molehills – An attempt at disruption, The Red Mole, vol.2, no.14, 14 August 1971. |