Eveline Lubbers, 17 September 2019

[Black Power – 1. Overview ] [Black Power – 2.Groups] [Black Power – 3. Special Branch Files in context][Black Power – 4. Black Power Desk]

The files on the Black Power movement presented here come from the National Archives, with one important exception. This article explains our selection, and details our battle with the Home Office which – once again – classified a file that had previously been released to others under the Freedom of Information Act. This is a recurring practice with material covering police and intelligence issues, we wrote about it before – in fact the SpecialBranchFiles.uk project was set up to fight this.

The National Archives holds many files on this topic from a number of different sources, the Home Office (HO), the Metropolitan Police (MEPO), the Director of Public Prosecution (DDP), the Central Criminal Court (CRIM) and the Cabinet Office (CAB).

To get an idea of what kind of information Special Branch gathered about the Black Power Movement, one needs to go through reports prepared by the Met on specific events, as well as through legal papers from the various court cases brought against key people. As our article Black Power, Special Branch files in context shows, sometimes Special Branch officers provided evidence in court cases and were asked to explain about their job gathering intelligence about ‘subversive elements’. Occasionally, the Home Office would bring together reports from various sources to inform the Secretary of State, for instance about the demonstration that would lead to the trial of the Mangrove Nine.

Going through the Home Office archive is not an easy job though, as the way it is organised is not as straight forward as one would hope. However, bringing together files and comparing them also leads to interesting discoveries.

There was one file did have our specific interest, as it was quoted by others writing about the Black Power Movement. However, these files, ‘Black Power’ intelligence reports 1968-1977 are ‘retained by a government department‘ and therefore not available in the National Archives. We submitted a Freedom of Information request with the Home Office for file HO 376/154 and 155, explaining in detail that the files had already been released to others, and where they had been quoted.

Disappointingly, the Home Office refused to release the files to us, apart from two publicly available press clippings the size of a postage stamp.

We appealed and asked for an internal review, arguing that the fact that the files had been released before had not been addressed at all. In their response, the HO explained that ‘in 2015 the files were reviewed as part of the normal periodic process and said that after consulting ‘third parties’ (without defining who these would be), it was decided that that ‘due to ongoing sensitivities with the material it should be withheld from future release’.

Responding to our principle point that ‘information released under the FOI Act is released to the world’, their answer was ambiguous to say the least, allowing wriggle room (and by bringing up the Information Commissioner, discouraging us to take our case there):

Whilst the Home Office acknowledges that if something is released to one person it is

releasable to everyone, the Information Commissioner accepts that public authorities can change their view over a release if they believe it is in the public interest to withhold.

However, this was not the end of our quest. In the meantime, we had found a scholar whose FoI request for these files had been successful in 2010 – partly at least. Robin Bunce, with Paul Field author of a biography of Darcus Howe, was kind enough to share with the Special Branch Files project the extracts that had been released to him.

Looking at the files, one wonders why they have been reclassified, and what the ‘ongoing sensitivities of third parties’ would be relating to events of 50 years ago. In the last sentence of their letter to us, the Home Office says that though their decision might be disappointing, ‘I do assure you that the withholding of the information is in the overarching public interest’.

Now that was utter nonsense, as our research would show.

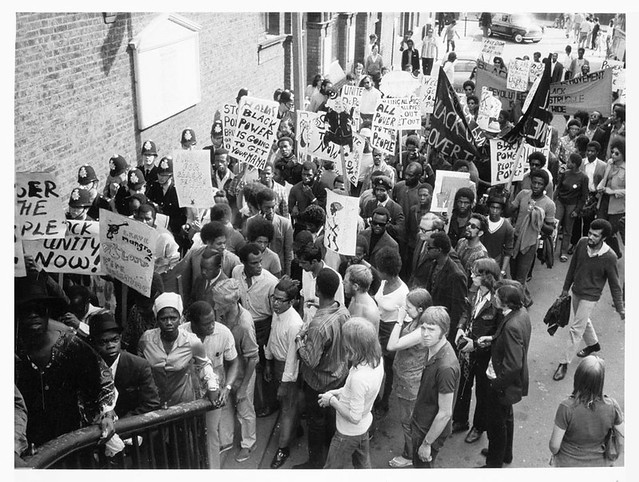

The material released to Bunce includes three reports about a key moment in the history of the Black Power movement in Britain: the 9th August, 1970 demonstration protesting the raid on the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill that was provoked into a confrontation with the police.

The first file includes a more general SB report on Black Power in the UK and an appraisal by the Met’s Community Relations division (A.7) of the ‘racial aspects’ of the events, both written two days after the evem. The second file consists of some correspondence about the revision of a report by the Joint Intelligence Committee on the Black Power Movement in 1968, disclosing no more than the introduction of it.

Further information is withheld under section 23(1) of the FoI Act, ‘where it was supplied by, or relates to, bodies dealing with security matters’, Bunce was told. ‘Please note, however’, the Home Office continues, ‘that, in spite of the fact that both files are entitled Black Power: intelligence reports, most of the withheld material does not concern the black power movement’.

When we asked for the same files, however, further grounds for refusal were given: disclosing personal information would contravene the new General Data Protection Regulation, while releasing the files could also endanger ‘national security’ – section 24(1). Whether section 23 or 24 applied, the HO refused to say, as that in itself would disclose secret information. (If that was not enough, section 27(1) and 31(1)(a) were also called into play.)

Weirdly enough though, on close inspection, the reports on Black Power disclosed to Bunce and refused to us can all be found in another Home Office file. And more than that, the versions there do include names of high level Special Branch officers and ditto civil servants that were redacted in Bunce’s sets of files. (See HO 325 143: SB Report August 9, 1970, SB Report on Black Power and A.7 Report on Racial Aspects.) Additionally, a full copy of the final 1968 JIC Report – of which Bunce only received the intro – is available in the Cabinet files, also held at the National Archives.

It was not like the alternative availability of the retained files was a secret.

On the contrary, the National Archives organised a well-publicised event in 2016 ‘Rights, resistance and racism: the story of the Mangrove Nine‘. They invited key people like Althea Jones-Lecointe, leader of the British Black Panther Movement, Eddie Lecointe, a key campaigner, and Barbara Beese, another of the original Mangrove Nine as well as family members of Frank Crichlow, the owner of the Mangrove restaurant, to show them how Special Branch had reported on them back in the day.

All in all, this seems to be yet another example of misplaced secrecy, and of rolling back the transparency that the Freedom of Information Act was meant to accomplish. The Special Branch Files Project discovered other examples of this worrying trend before; sharing previously disclosed files made secret again has been one of the main reasons to set up this site.

A discovery in this case, is that the Home Office ‘Information Rights Team’ does not appear to have the necessary overview to properly deal with requests for information.

The files presented here are a first selection, just the ones that have been quoted in our four articles on Special Branch and Black Power. More files will be added later.

———————————————–

Remember, these are only the files that the authorities chose to disclose and may only represent a small fraction of the total files held. Also, what police officers report to their superiors is not necessarily true.