Rosie Wild and Eveline Lubbers, 17 September 2019

[Black Power – 1. Overview ] [Black Power – 2.Groups] [Black Power – 4. Black Power Desk][Black Power – 5. Files overview, and another FoI battle]

The British state took the threat of Black Power very seriously, both at home and across the Commonwealth. When an international conference on Black Power took place in British Protectorate Bermuda on July 10-13 July 1969, the British government sent a warship full of marines to anchor off the coast in case civil disorder broke out and Special Branch officers attended, submitting a 133pp report afterwards.

Beforehand, the option to ban the entire conference had been discussed up to the level of the Prime Minister in the UK. The fact that there was no law that could be used to do such a thing, and that it would be impossible to enforce a ban, was seen as a minor issue set against the risks of UK military involvement should disturbances occur.[1]See PREM 13/2885: ‘Bermuda: Black Power conference, July 10–13, 1969’ and FCO 44/195: ‘“Black Power” political activities 1969’, both held in the National Archives.

While both Special Branch and the government’s Joint Intelligence Committee did not believe that Black Power would ever become widely supported by black people in the UK, they did worry about its potential to inspire civil unrest.

Could it happen here?

From the mid-1960s the spectre of black uprisings, of the sort blazing across major northern American cities, haunted the British press and parliament. ‘Could it happen here?’ asked the media publicly and the Home Secretary in private. Predicting that that the first generation of British-born black children, reaching school-leaving age from the start of the 1970s, would not put up with the clearly discriminatory conditions their immigrant parents had, the government’s Joint Intelligence Committee thought the answer might well be yes.[2]See report ‘Joint Intelligence Committee: Black Power’, 28 February 1968, in CAB 158/68, held at the National Archives. Two earlier drafts of the introduction only, dated 8 February and 28 February can be found in HO 376/154 held closed at the National Archives and partly released under a Freedom on Information request to historian Robin Bunce in 2010.

Fear of American-style rioting in British cities, as well as a Cold War concern about the Russian and Chinese Communist Parties using UK Black Power groups (all of which were avowedly Marxist-Leninist) as a proxy, meant Black Power activists were classified as subversives to be spied on and disrupted.[3]The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), conversely, was not interested in making links with British Black Power groups. It regarded Communists who Black Power activists admired, like Trotsky, Che Guevara and Mao, as dangerous dissidents. An internal memo shows the CPGB was also unimpressed by Stokely Carmichael’s comment that ‘Marx was a honkie, and we don’t want black people looking up to no white man no matter who he is.’ See R Wild, ‘Black was the Colour of Our Fight: Black Power in Britain 1955-1976′, PhD dissertation (2008), p. 150. Although it is likely that Special Branch was monitoring the antics of Michael X from 1965, it definitely started collecting intelligence on Black Power after the visit of Stokely Carmichael in July 1967. The Home Office holds closed ‘“Black Power” intelligence reports’ from 1967 right up to 1981, long after the movement had ceased to exist in any meaningful sense.[4]See catalogue description of file HO 376/154, in the National Archives.

Hyde Park

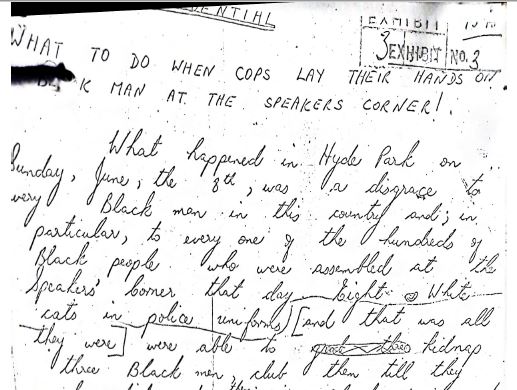

During the summer of 1967 Special Branch officers mingled with the Sunday crowds listening to Universal Coloured People’s Association (UCPA) members discoursing on white oppression and black resistance at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park. Detective Sergeant G. Battye‘s and Detective Sergeant Francke‘s transcribed shorthand notes from speeches over successive August 1967 weekends were used as the evidence in one of the UK’s first prosecutions for inciting racial hatred. UCPA and RAAS members Roy Sawh, Ajoy Ghose, Alton Watson and Michael Ezekiel were convicted in November 1967.[5]See DPP 2/4428: WATSON, Alton, SAWH, Roy, GHOSE, Ajoy, EZEICIEL, Michael, “Racial Adjustment Action Society” and “Universal Coloured People’s Association”: s 6(1) Race Relations Act 1965. Using threatening abusive, or insulting words in Hyde Park, London, 6 August 1967, held at the National Archives

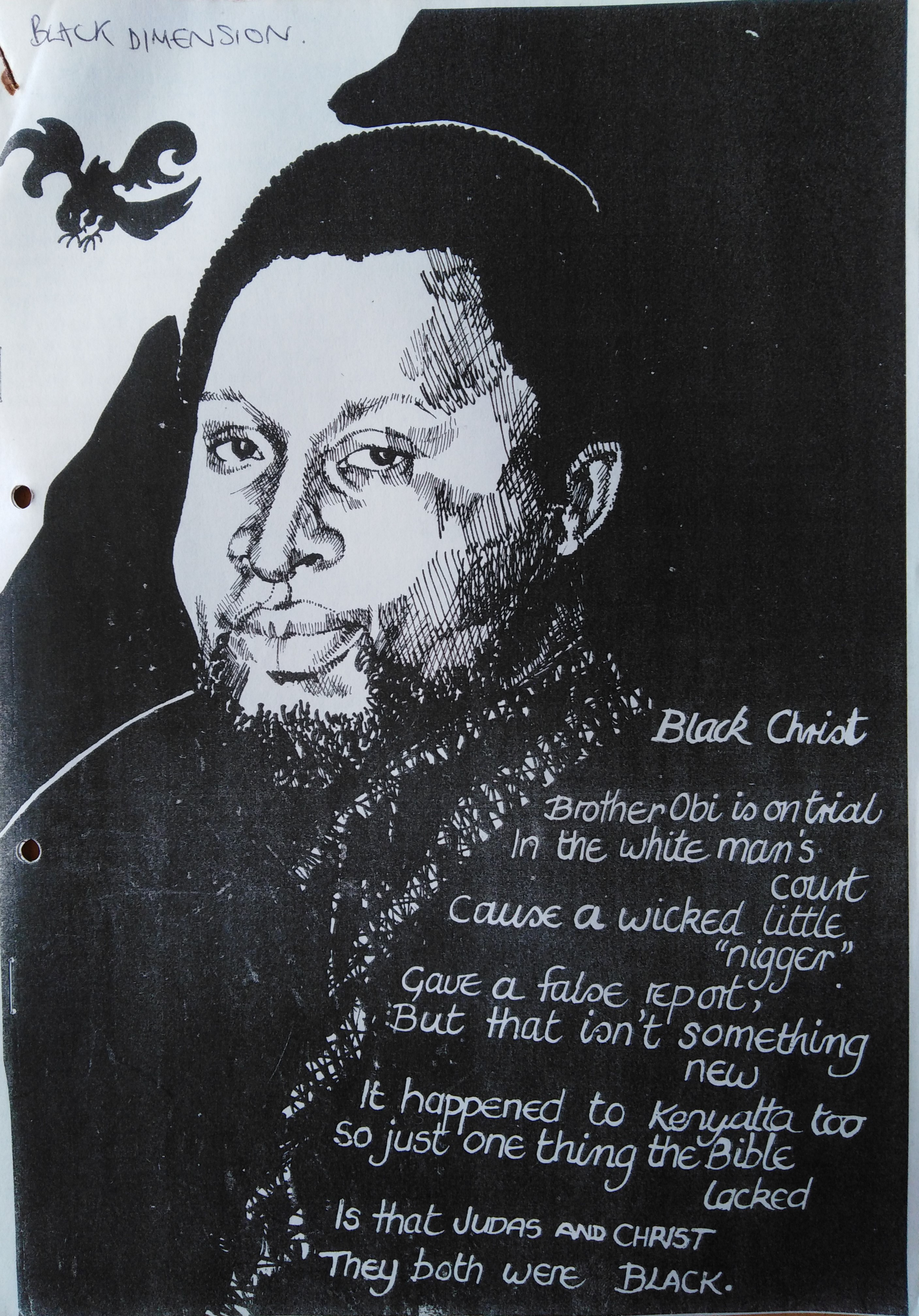

In 1968, Special Branch gathered evidence to support the prosecution of UCPA and Black Panther Movement (BPM) founder Obi Egbuna and fellow activists Peter Martin and Gideon Dolo. [6]Egbuna was arrested the day before the BBC was finally going to air a shocking documentary about police violence against black people. The Met had tried everything they could to prevent this and it is possible that Egbuna’s arrest was deliberately timed so that the police could attempt to stop the TV show being aired by claiming it would prejudice his case. If that was the plan, it didn’t work. For more, see: Robin Bunce, ‘Darcus Howe and the extraordinary campaign to expose racism in the police’, The New Statesman, 7 January 2014

All three spent five months on remand before being tried for inciting murder in December 1968, after a draft of a rather florid leaflet written by Egbuna was handed to the police by the printer of Black Power Speaks.[7]For further details of the prosecution see MEPO 2/11409: ‘Benedict Obi Egbuna, Peter Martin and Gideon Ketueni T. Dolo charged with uttering and writing threatening [sic] to kill police officers at Hyde Park, W2’, held at the National Archives. Egbuna was given a three-year suspended sentence. Commending his officers, Detective Chief Inspector (DCI) Kenneth Thompson wrote, ‘The arrest of Egbuna . . . at this stage anyway, put the [Black Panther] party in confusion and it is not likely to resurrect for many months to come.'[8]Quoted in P. Field, The Real Guerillas, Jacobin, 14/4/2017.

A month later, a dozen Special Branch officers went undercover as demonstrators during a large march against apartheid co-organised by the Black People’s Alliance.[9]Elwyn Jones of Special Branch testified under cross examination during the trial of Edward Davoren that there were ‘between ten and a dozen’ Special Branch officers dressed as demonstrators on the 12 January 1969 march to protest against Apartheid during the 1969 Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference in London. See CRIM 1/5146: ‘DAVOREN, Edward Michael and others. Charge: Riot and assault on a constable held in the National Archives.

No black police officers

Blending into a multi-racial crowd of onlookers or demonstrators was one way of gathering information, infiltrating Black Power groups, however, proved almost impossible. This was because the Metropolitan Police, having spent years actively preventing black people from joining the force, found itself with no black officers available to go undercover in the Black Power movement.[10]Internal memo to the Commissioner of Police dated 10/12/1963 in MEPO 2/9854: ‘Police liaison with the West Indian community in London’, held at the National Archives. The memo reads ‘The truth is, of course, that we are not yet prepared to recruit any coloured men…'

The first black policeman in the UK was Astley Lloyd Blair, who joined the Gloucestershire constabulary in 1964. It took three more years for the Metropolitan Police to hire its first black officer, Norwell Roberts, in 1967. He was joined by Britain’s first black policewoman, Sislin Fay Allen, in 1968. In August 1973, by which time the Black Power movement was in serious decline, Home Office figures revealed there were still only 65 black police officers in the whole of England and Wales.[11]Police/Immigrant Relations in England and Wales: Observations on the Report of the Select Committee on Race Relations and Immigration (London: HMSO, 1973), p. 11.

So far, the official Undercover Policing Inquiry has released the cover name of one officer who may have tried to infiltrate the Black Power Movement, among other groups. The name he used was ‘Peter Fredericks’ and he described himself as ‘mixed race’. The Inquiry has stated that he was not deployed against any one specific group but reported back on an number, including those opposed to apartheid in South Africa, the Black Power movement, and two other small ones, Operation Omega and Young Haganah. He was active for only six months in 1971, as opposed to four or five years which was standard for undercover operations of the Special Demonstration Squad. His deployment ceased when his probationary period in Special Branch was terminated; it is unclear why.[12]The Chair of the Inquiry said about this: ‘There is a difference between his recollection of the reason for termination and that recorded in his personnel file. He left the Metropolitan Police Service soon after.’ See, John Mitting, SDS anonimity, Minded to note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry I,14 November 2017. All in all, the Inquiry makes it sounds like this undercover operation was aborted before it really took off, and never got beyond reporting on meetings and demonstrations attended.

Informants

Informants were a different matter, and it is likely that this was one of the main ways Special Branch gathered intelligence about Black Power groups, along with surveillance. ‘The members of the Black Panther Party [sic] were the subject of prior investigation and observation and every one of the officers mentioned showed outstanding enthusiasm and detective ability’, explained a Special Branch memo relating to the prosecution of Obi Egbuna in 1968, ‘It is right to mention that there was excellent cooperation between Special Branch and the passport squad.'[13]See p. 15, Met Police Criminal Investigation Dept 1/8/68 ref 203/68/74 by Det Chief Inspector Thompson in: Benedict Obi EGBUNA, Peter MARTIN and Gideon Turagalevu DOLO: charged with circulating writings at Speakers’ Corner, Hyde Park, threatening to kill and maim police officers, involvement of the above-named with ‘Black Panther’ Party. In MEPO 2/11409, held at the National Archives.

The same memo also refers to ‘reliable information from an informant within the organisation of the Black Power Group [sic]…’ that ‘they were training in the use of explosives and firearms and although a cache was known to exist to date it has not been found.'[14]Also in MEPO 2/11409.

How reliable this information was, given that no weapons were ever found and the Black Panther Movement in Britain never used firearms or explosives, is a matter for debate. Certainly it would have suited Special Branch to portray Egbuna as an aspiring domestic terrorist, both to inflate the importance of its own work and to ensure a hefty sentence for him.

Activists within Black Power groups often suspected there were members who leaked information to the police or could even be plants. ‘[W]e were pretty sure at the time that in the UCPA there were two who were linked to the police. At the very least they were informers’, explained Tony Soares, ‘And later as well in Grass Roots there was one person I was sure had been sent in.[15]Tony Soares interview with Rosie Wild, 17 September 2004. Soares may well have been correct. The man in question later held a position in the BPM, where we know Special Branch also had access to an informant.

A memo contained in the Metropolitan Police’s notes on the Mangrove trial in 1971 reveals that there was definitely an informer, possibly a photographer for Ajoy Ghose’s Notting Hill-based magazine Tri-Continental Outpost who agreed to provide police with photographs of Black Power marches from August 1970 onwards.[16]See memo from from Chief Inspector R Radford: ‘Photographs relating to demonstration on Sunday 9th August, 1970’, dated 11/7/1970 in MEPO 31/20: ‘Black Power’ demonstration on 9 August 1970: France, L and 18 Others arrested for assault on police and other offences in Portnall Road and Shirland Road, W9. Critchlow, F acquitted of charges of riot and affray. Reports, statements and correspondence, held at the National Archives.

Another indication pointing at the use of informers or undercover officers can be found in two cover notes to reports on the Mangrove Nine trial, sent by MI5 to the Home Office. In the notes, the Secret Service emphasises that some of the intelligence is coming from secret and delicate sources, and that the reports are thus classified SECRET.[17]Note from MI5 [author redacted] to Mr Hilary at the Home Office, 31 December 1971. The second reference is atached to a letter, dated 25 January 1972, giving information on the nine defendants. The cover not explains that the first paragraph of gives a brief resumé of the court case based on information from the press, but then states that ‘Security information is given in paragraph two, and as some of this comes from delicate sources requiring protection the notes are graded secret.’ See HO 325 143, held at the National Archives.

One specific section in the MI5 memo ‘The Trial of the Mangrove Nine’ contains information that has not been not mentioned before in the press or in police reports, according to the Home Office official responsible for Special Branch, D McQueen. The section recounts ‘a remarkable celebration’ at the end of the trial ‘with jurors buying the acquitted defendants drinks’. ‘The two black jurors are known to have been taken to the Black Panthers Headquarters for a celebration.’[18]See HO 325 143, held at the National Archives.

This specific piece of intelligence could come from surveillance or from informants or undercover officers – though, if the latter, it remains unclear whether they were working for MI5 or Special Branch.

A further potential source of information was the crossover between Black Power groups and heavily infiltrated left-wing groups such as the International Marxist Group (IMG) and the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front (INLSF).[19]For more on this cooperation, see the articles Black Power – 2. Main Groups and Special Branch and the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front.

The MI5 report quoted above, for instance, mentioned the founding of the ‘Mangrove Trial Defence Comittee’ and specifies that ‘monies have been contributed by several left groups including the Spartacus League (Trotskyists’.)[20]See HO 325 143, held at the National Archives. Rather than from an informant in the Black Power movement, this piece of intelligence seems to originate from someone reporting on the Spartacus League.

Note that MI5 had the name wrong, mixing up ‘the Black Defence Committee’ and the ‘Black Defence and Aid Fund’ The report also fails to mention that both had been set up by the IMG and were based at their offices. The IMG had at least five different undercover officers from the Special Demonstration Squad deployed in the organisation between the late 1960s and the mid 1970s, and further agents in groups linked to it.[21]See Spycops Targets, a Who’s Who for the cover names of officers who infiltrated the IMG and other groups. Indeed, Special Branch was aware of the Black Defence Committee from the moment of its inception, and knew that it was formed by the Spartacus League – the youth section of the IMG. As this Special Branch report shows, they also had a lot of detail on which groups was supporting the Committee:

It seems likely that the piece of intelligence on the contributed monies came from one of the undercover officers. However, it remains unclear how intelligence gathered by Special Branch ended up in an MI5 report in such a summarised form – and with the omission of such an important detail.

For more on the issue of cooperation between Special Branch and MI5 see 4. The Black Power Desk.

Although the white undercover policemen in left-wing groups were not able to join Black Power groups, they could provide information about jointly organised marches, funds given to Black Power groups in solidarity and how well Black Power and white groups were working together on issues of common interest, such as civil rights in Northern Ireland. As Black Power groups like the Black Panther Movement moved more towards a class-based rather than race-based analysis of society in the early to mid-1970s, these streams of intelligence would have been valuable.

Foreign agents

Special Branch also shared and received information with British and foreign intelligence services.

Special Branch monitored ‘subversive’ US citizens who visited the UK and from 1967 reported on when these people met with Black Power activists.[22]A February 1968 report on ‘American political activity in London‘ authored by Sergeant P Radford records UK Black Power activists meeting with rights leader Floyd McKissick, left-wing historian George Rawick and civil rights activist and comedian Dick Gregory. In HO 325/104, held at the National Archives. BUFP activist Lester Lewis believed the group was infiltrated by someone he later found out was a CIA agent: an African American woman called Connie who was very interested in the group’s links with African liberation movements and who later moved to Angola.[23]Interview with Rosie Wild, 14/9/2004.

The Joint Intelligence Committee met more than once to discuss Black Power in late 1967. Their report, which was informed by intelligence from both Special Branch and MI5, appeared in final form in February 1968. It was circulated to the FBI, the CIA, and other allies and missions all around the world.[24]See ‘JIC 68(8) Black Power‘ in CAB 158/68.

Covert propaganda

The Foreign Office sent a report on The Black Power Movement in Britain to the Immigration Department at the Home Office in July 1970, an update from their June 1969 report.[25]The Black Power Movement in Great Britain, FCO 95/792, held at the National Archives.

The reports were compiled by the Information Research Department (IRD), a secret propaganda unit set up against the backdrop of the cold war to counter ‘communist influences’. The IRD ‘placed unattributed articles in the press both in the UK and abroad, and […] covertly published books and academic articles, produced radio programmes, ran news agencies and influenced the BBC and Reuters’.[26]Ian Cobain, Wilson government used secret unit to smear union leaders, The Guardian, 24 July 2018

Files recently released by the National Archives revealed that senior figures in Harold Wilson’s Labour government plotted to use the IRD to smear a number of left-wing trade union leaders in 1969.[27]Ian Cobain, Wilson government used secret unit to smear union leaders, The Guardian, 24 July 2018. Also see, Information Research Department, Powerbase, last updated November 2017, for operations in Indonesia, and Nothern Ireland, and against the BBC.

It is unclear to what the extent the IRD was involved with the Black Power Movement in the UK around that time. According to the confidential cover note, a copy of the IRD’s 1970 paper on Black Power Groups was sent to Mr Platt of the Home Office ‘whose section vetted the original paper’.

Mr. Platt’s section is the unit in Whitehall charged with the oversight of race relations in this country and I think that we should take care to carry them with us in this occasion. […] Thereafter the paper might be sent, for a start, to all the recipients of British Communist Activities.

The IRD clearly aimed to have the Home Office on board with whatever they were planning.

In that period, the IRD was indeed very active in countering the influence of radical black groups in the run up to the Black Power conference in Bermuda (mentioned above). The Foreign Office wanted to ‘implement “informed” countermeasures’ and its IRD gathered ‘information from the Security Service and U.S officials about the operations and finances of Black Power organisations, advocates and activities in the Caribbean and U.S. and those who might attend the Conference.'[28]Quito Swan, Black Power in Bermuda: The Struggle for Decolonization, Springer, 2009, pp59-60. Open repression against the growing influence of what the author calls the Black Power Cadre was considered unwise, as it would potentially raise the tensions. Hence, the FCO launched a covert campaign to surpress Black Power. Swan, p124, also see pp125-128, 130-132.

Another example of covert propaganda involves the foreign intelligence service, MI6. We now know that glossy magazine Flamingo which targeted Britain’s African-Caribbean community and ran from 1961 to 1965 was funded by MI6 in order to promote anti-communism to the black community.[29]See Jamie Doward, ‘Sex, ska and Malcolm X: MI6’s covert mission to woo West Indians’ in The Observer, 26 January, 2019, accessed 20/6/19.

Black Power Desk

Many files on Black Power groups in the UK are still retained in the National Archives. Special Branch must have done more than keeping notes of Hyde Park speeches and reported on Americans in London in the late 1960s. British Black Power was also monitored via a dedicated Black Power Desk, which was either a Special Branch affair or resided at the Britain’s intelligence service MI5.

The file ‘The Trial of the Mangrove Nine’ quoted above in the section about informants, was sent to the Home Office by someone in the Secret Service noting they had just taken over the Black Power Desk. This is the only known mention of the Desk in the files currently available at the National Archives. (For more detail see 4. Black Power desk.)

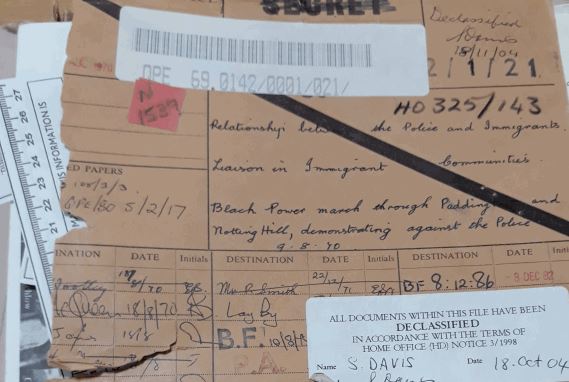

In response to the Mangrove march that had seen Black Power protesters clash violently with police in Notting Hill in August 1970, Home Secretary Reginald Maudling asked for an up to date report on the events and their significance. It came replete with legal advice on the best strategy for smashing the movement.[30]See HO 325/143.

Two days after the march, Maudling told The Guardian that, ‘The Special Branch has had the movement under observation for more than a year’.[31]Peter Harvey & John Cunningham, Black Power file for Maudling, The Guardian, 12 August 1970, p. 3.

It is striking, however, how little the August 1970 Special Branch report seems to reflect the changed landscape of British Black Power since 1968. This suggests that Special Branch had not paid too much attention to Black Power in the intervening years. Still focusing on characters like Michael X who were peripheral to the more grass-roots approach to Black Power organising taking hold in the early 1970s, Special Branch’s intelligence-gathering was behind the curve.[32]See HO 325/143.

The report’s two appendices listing the major figures and organisations in the movement show that Special Branch had virtually no information about the Black Panther Movement and was not aware that a faction of the UCPA had split off to form the Black Unity and Freedom Party in July 1970.[33]See HO 325/143.

Police as ‘the real victims’

What the report and correspondence around it does show was that Special Branch, in common with the rest of the Metropolitan Police, was furiously opposed to any suggestion that the police’s behaviour towards black people might be a contributing factor in worsening race relations.

Characterising all Black Power campaigning about police racism as disingenuous rabble-rousing, Special Branch consistently portrayed the police as the real victims of harassment. An extract from Appendix A of its August 1970 report thus describes ‘an incident on Portobello Road, on 10.7.69 when the police were severely harassed following an accident when an out-of-control Police vehicle fatally injured a coloured man‘.[34]Appendix A, “Black Power” Organisations in the United Kingdom’ of the Special Branch report “Black Power” in the United Kingdom in HO 325/143. Local bystanders becoming upset that a police vehicle had just killed someone in their midst was no doubt part of the ‘intemperate “anti-police” campaign’ that Special Branch warns about earlier in the report.[35]See HO 325/143.

It was probably much easier to gather intelligence on Black Power in its initial phase, as leaders like Michael X, Roy Sawh and Obi Egbuna were publicity-hungry. By 1971 the first wave of leaders had been replaced by a much lower key bunch, committed to community organising and much more disciplined in their organisation and secrecy. Nonetheless, Special Branch continued to have noticeable successes in disrupting Black Power groups and ‘decapitating’ them by tying up their leaders in lengthy criminal prosecutions in the early to mid-1970s.

The Mangrove Nine and Grass Roots trials

Two major trials – the Mangrove Nine in October-December 1971 and Tony Soares’ Grass Roots trial in March 1973 – were brought about with significant input from Special Branch. Stemming from the 9 August 1970 Hands Off The Mangrove protest march, the Mangrove Nine trial saw nine Black Power activists, among them Darcus Howe and BPM leader Altheia Jones-Lecointe, prosecuted for riot, affray and assaulting police officers.

The police had some catching up to do in trying to build cases against the most prominent activists from the two dozen originally arrested after the demonstration. In their biography of Darcus Howe, Robin Bunce and Paul Field write: ‘For nine weeks before the charges were brought, the energies of sections of the Metropolitan Police and Special Branch were devoted to gathering ‘evidence’ to persuade a jury that leading members and key allies of the Black Power Movement […] were implicated in planning and inciting the riot on 9 August 1970.’ The authors make a case that the authorities were trying to undermine Black Power in Britain in every way they could.

It was not a coincidence that out of 23 people arrested on the march, those particular nine stood trial; they had been picked out from surveillance photographs taken by an undercover police photographer. Some were not even arrested on the march but picked up weeks afterwards.[36]One defendant, Rothwell Kentish, was arrested by four policemen at the garage where he worked on 14 October 1970, six weeks after the march. He resisted arrest because the police did not have a warrant in his name and he claimed that he had left the march by the time the clash with the police took place. Subsequently acquitted of all charges during the Mangrove trial, he was, however, separately convicted of assaulting a police officer and carrying offensive weapons (the hammer, welding equipment and wire cutters he had been using at work) – charges resulting from his October 1970 arrest.

The eleven week trial became a cause célèbre after several of the activists chose to defend themselves and were acquitted. At the end of the trial, five of the defendants – Rothwell Kentish, Frank Critchlow, Radford Howe, Barbara Beese and Godfrey Millet – were acquitted of all charges. The other four – Anthony Innis, Rhodan Gordan, Altheia Jones-Lecointe and Rupert Boyce – received suspended sentences for seven of the less serious charges. During sentencing, Judge Clarke remarked that ‘What this trial has shown is that there is clearly evidence of racial hatred on both [i.e.police and protesters] sides’. He was later summoned to the Home Office to explain his remarks, after the Metropolitan Police reacted with outrage.[37]See MEPO 2/9719: ‘Racial incidents: relations between the police and the black community in the Notting Hill area’, held at the National Archives.

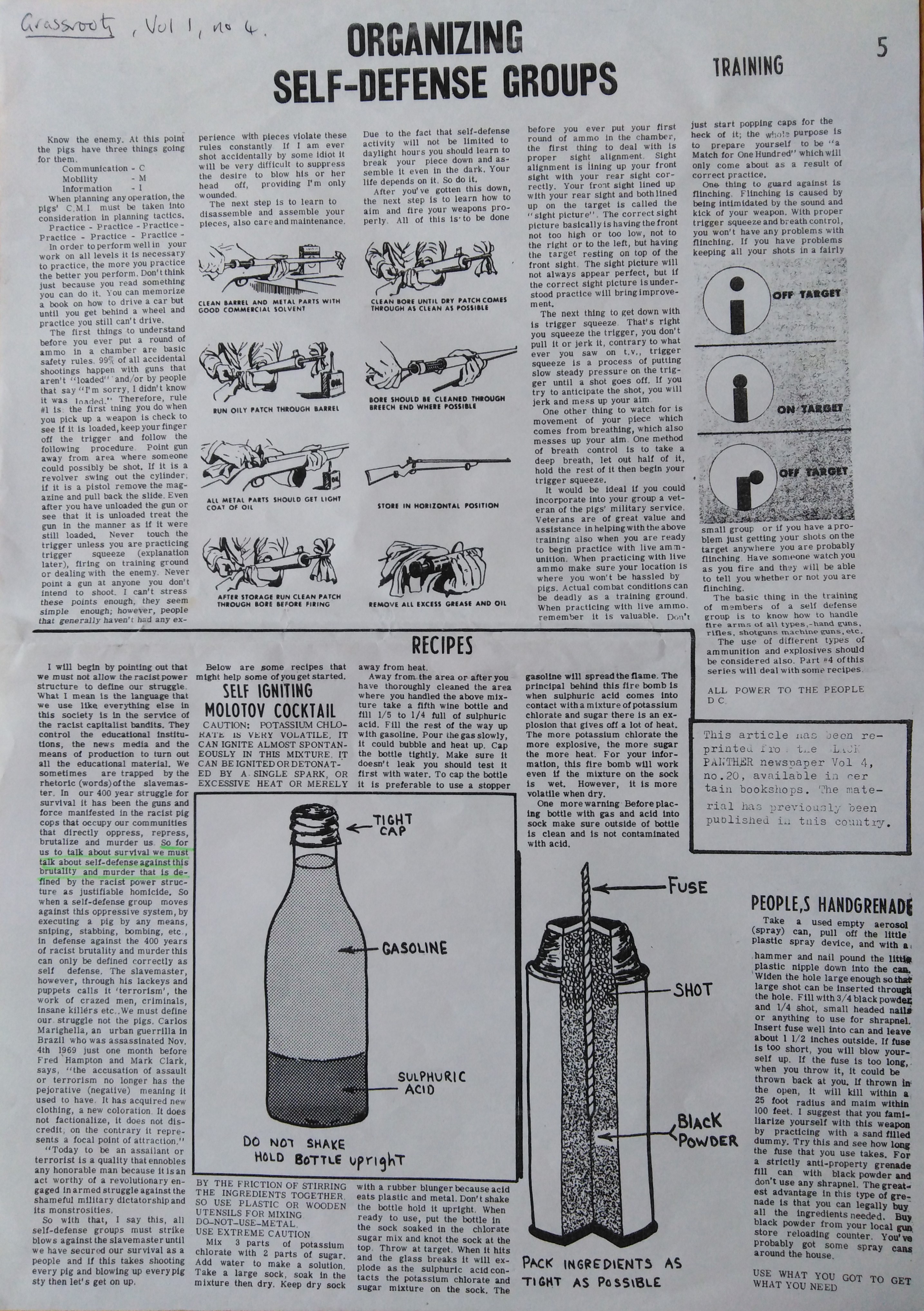

Soares was arrested on 9 March 1972 after Special Branch raided the office of the BLF newspaper Grass Roots and seized the September 1971 issue which contained reprinted instructions on how to make a Molotov cocktail. He was charged with incitement to murder and several other terrorist offences, and spent four months on remand before being released on bail. His trial at the Old Bailey eventually started in March 1973 and featured Special Branch officers sitting in the front row of the observers’ gallery noting down the names and addresses of all Soares’s witnesses.[38]‘Dock brief’, Race Today 5:4 (April 1973) p. 102. He was convicted, pivotally, because of Special Branch-supplied evidence that he had ‘distributed’ 25 copies of the September 1971 issue of Grass Roots overseas.[39]See A. Angelo, ‘”We All Became Black”: Tony Soares, African-American Internationalists, and Anti-imperialism’, in The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the United States, eds R. D. G. Kelley and S. Tuck, p100.

Black Power activist Winston Trew suspected the hand of Special Branch in his and three other members of the Fasimbas’ arrest by undercover transport police officers at Oval tube station a week after Tony Soares’ arrest. The four were travelling back from the BLF headquarters where they had attended a planning meeting to publicise his legal problems.[40]See Winston Trew, Black for a Cause, The British State, Special Branch and Black Power, no date, accessed 21/6/19. As his arresting officer, Detective Sargeant Derek Ridgewell, was later revealed to be a deeply corrupt officer who regularly falsely accused young men of theft on the London Underground. Trew now believes he and his friends may not have been targetted by Ridgewell for political reasons. Ridgewell died in prison in 1982.

Serious threat

By 1973, Black Power in Britain was a movement on the wane. Special Branch’s campaign against Black Power had chalked up some notable successes. Even though its 1970 report had described Black Power as ‘a concept and term that has been given an exaggerated sense of importance out of all perspective‘, the evidence suggests Special Branch treated Black Power as a serious threat, to which it gave a robust response.[41]See HO 325/143.

References

| ↑1 | See PREM 13/2885: ‘Bermuda: Black Power conference, July 10–13, 1969’ and FCO 44/195: ‘“Black Power” political activities 1969’, both held in the National Archives. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See report ‘Joint Intelligence Committee: Black Power’, 28 February 1968, in CAB 158/68, held at the National Archives. Two earlier drafts of the introduction only, dated 8 February and 28 February can be found in HO 376/154 held closed at the National Archives and partly released under a Freedom on Information request to historian Robin Bunce in 2010. |

| ↑3 | The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), conversely, was not interested in making links with British Black Power groups. It regarded Communists who Black Power activists admired, like Trotsky, Che Guevara and Mao, as dangerous dissidents. An internal memo shows the CPGB was also unimpressed by Stokely Carmichael’s comment that ‘Marx was a honkie, and we don’t want black people looking up to no white man no matter who he is.’ See R Wild, ‘Black was the Colour of Our Fight: Black Power in Britain 1955-1976′, PhD dissertation (2008), p. 150. |

| ↑4 | See catalogue description of file HO 376/154, in the National Archives. |

| ↑5 | See DPP 2/4428: WATSON, Alton, SAWH, Roy, GHOSE, Ajoy, EZEICIEL, Michael, “Racial Adjustment Action Society” and “Universal Coloured People’s Association”: s 6(1) Race Relations Act 1965. Using threatening abusive, or insulting words in Hyde Park, London, 6 August 1967, held at the National Archives |

| ↑6 | Egbuna was arrested the day before the BBC was finally going to air a shocking documentary about police violence against black people. The Met had tried everything they could to prevent this and it is possible that Egbuna’s arrest was deliberately timed so that the police could attempt to stop the TV show being aired by claiming it would prejudice his case. If that was the plan, it didn’t work. For more, see: Robin Bunce, ‘Darcus Howe and the extraordinary campaign to expose racism in the police’, The New Statesman, 7 January 2014 |

| ↑7 | For further details of the prosecution see MEPO 2/11409: ‘Benedict Obi Egbuna, Peter Martin and Gideon Ketueni T. Dolo charged with uttering and writing threatening [sic] to kill police officers at Hyde Park, W2’, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑8 | Quoted in P. Field, The Real Guerillas, Jacobin, 14/4/2017. |

| ↑9 | Elwyn Jones of Special Branch testified under cross examination during the trial of Edward Davoren that there were ‘between ten and a dozen’ Special Branch officers dressed as demonstrators on the 12 January 1969 march to protest against Apartheid during the 1969 Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference in London. See CRIM 1/5146: ‘DAVOREN, Edward Michael and others. Charge: Riot and assault on a constable held in the National Archives. |

| ↑10 | Internal memo to the Commissioner of Police dated 10/12/1963 in MEPO 2/9854: ‘Police liaison with the West Indian community in London’, held at the National Archives. The memo reads ‘The truth is, of course, that we are not yet prepared to recruit any coloured men…' |

| ↑11 | Police/Immigrant Relations in England and Wales: Observations on the Report of the Select Committee on Race Relations and Immigration (London: HMSO, 1973), p. 11. |

| ↑12 | The Chair of the Inquiry said about this: ‘There is a difference between his recollection of the reason for termination and that recorded in his personnel file. He left the Metropolitan Police Service soon after.’ See, John Mitting, SDS anonimity, Minded to note 2, Undercover Policing Inquiry I,14 November 2017. |

| ↑13 | See p. 15, Met Police Criminal Investigation Dept 1/8/68 ref 203/68/74 by Det Chief Inspector Thompson in: Benedict Obi EGBUNA, Peter MARTIN and Gideon Turagalevu DOLO: charged with circulating writings at Speakers’ Corner, Hyde Park, threatening to kill and maim police officers, involvement of the above-named with ‘Black Panther’ Party. In MEPO 2/11409, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑14 | Also in MEPO 2/11409. |

| ↑15 | Tony Soares interview with Rosie Wild, 17 September 2004. Soares may well have been correct. The man in question later held a position in the BPM, where we know Special Branch also had access to an informant. |

| ↑16 | See memo from from Chief Inspector R Radford: ‘Photographs relating to demonstration on Sunday 9th August, 1970’, dated 11/7/1970 in MEPO 31/20: ‘Black Power’ demonstration on 9 August 1970: France, L and 18 Others arrested for assault on police and other offences in Portnall Road and Shirland Road, W9. Critchlow, F acquitted of charges of riot and affray. Reports, statements and correspondence, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑17 | Note from MI5 [author redacted] to Mr Hilary at the Home Office, 31 December 1971. The second reference is atached to a letter, dated 25 January 1972, giving information on the nine defendants. The cover not explains that the first paragraph of gives a brief resumé of the court case based on information from the press, but then states that ‘Security information is given in paragraph two, and as some of this comes from delicate sources requiring protection the notes are graded secret.’ See HO 325 143, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑18, ↑20 | See HO 325 143, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑19 | For more on this cooperation, see the articles Black Power – 2. Main Groups and Special Branch and the Irish National Liberation Solidarity Front. |

| ↑21 | See Spycops Targets, a Who’s Who for the cover names of officers who infiltrated the IMG and other groups. |

| ↑22 | A February 1968 report on ‘American political activity in London‘ authored by Sergeant P Radford records UK Black Power activists meeting with rights leader Floyd McKissick, left-wing historian George Rawick and civil rights activist and comedian Dick Gregory. In HO 325/104, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑23 | Interview with Rosie Wild, 14/9/2004. |

| ↑24 | See ‘JIC 68(8) Black Power‘ in CAB 158/68. |

| ↑25 | The Black Power Movement in Great Britain, FCO 95/792, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑26 | Ian Cobain, Wilson government used secret unit to smear union leaders, The Guardian, 24 July 2018 |

| ↑27 | Ian Cobain, Wilson government used secret unit to smear union leaders, The Guardian, 24 July 2018. Also see, Information Research Department, Powerbase, last updated November 2017, for operations in Indonesia, and Nothern Ireland, and against the BBC. |

| ↑28 | Quito Swan, Black Power in Bermuda: The Struggle for Decolonization, Springer, 2009, pp59-60. Open repression against the growing influence of what the author calls the Black Power Cadre was considered unwise, as it would potentially raise the tensions. Hence, the FCO launched a covert campaign to surpress Black Power. Swan, p124, also see pp125-128, 130-132. |

| ↑29 | See Jamie Doward, ‘Sex, ska and Malcolm X: MI6’s covert mission to woo West Indians’ in The Observer, 26 January, 2019, accessed 20/6/19. |

| ↑30, ↑32, ↑33, ↑35, ↑41 | See HO 325/143. |

| ↑31 | Peter Harvey & John Cunningham, Black Power file for Maudling, The Guardian, 12 August 1970, p. 3. |

| ↑34 | Appendix A, “Black Power” Organisations in the United Kingdom’ of the Special Branch report “Black Power” in the United Kingdom in HO 325/143. |

| ↑36 | One defendant, Rothwell Kentish, was arrested by four policemen at the garage where he worked on 14 October 1970, six weeks after the march. He resisted arrest because the police did not have a warrant in his name and he claimed that he had left the march by the time the clash with the police took place. Subsequently acquitted of all charges during the Mangrove trial, he was, however, separately convicted of assaulting a police officer and carrying offensive weapons (the hammer, welding equipment and wire cutters he had been using at work) – charges resulting from his October 1970 arrest. |

| ↑37 | See MEPO 2/9719: ‘Racial incidents: relations between the police and the black community in the Notting Hill area’, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑38 | ‘Dock brief’, Race Today 5:4 (April 1973) p. 102. |

| ↑39 | See A. Angelo, ‘”We All Became Black”: Tony Soares, African-American Internationalists, and Anti-imperialism’, in The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the United States, eds R. D. G. Kelley and S. Tuck, p100. |

| ↑40 | See Winston Trew, Black for a Cause, The British State, Special Branch and Black Power, no date, accessed 21/6/19. |