How a complaint by Members of Parliament about infiltration led to an accidental discovery – the paper trail.

Eveline Lubbers, March 2021

[2. Who was the secret source of Special Branch?] [3. Context: Special Branch and Corporate Intelligence]

Special Branch copied a commercial report in 1969 and presented it as their own, our research shows. While it is known that information from Special Branch ended up in the blacklisting files of the Economic League and later the Consultancy Association, there is no example so clear of the cooperation with an outside source the other way round.

In 1970, three Members of Parliaments complaint to the Home Secretary about police infiltrating meetings of the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), in particular their 1969 Annual General Meeting (AGM). Eager to explain that they did not have an officer at this meeting, Special Branch revealed they had received detailed information from ‘a commercially-produced report’. Further research shows that the material from this ‘well-tried source’ was copied word for word and subsequently presented as a Special Branch report.

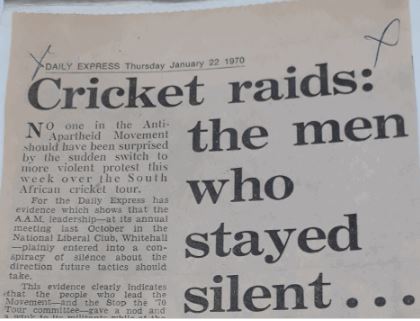

The main grievance of the MPs was the article Cricket Raids: the men who stayed silent, published on 22 January 1970 in the Daily Express, a paper known for its hostile position towards progressive groups. The article appeared just after dozens of cricket grounds had been disturbed as part of the campaign, with anti-apartheid slogans painted on the scoreboards and weedkiller spread on the fields.[1]Samuel Brook, When apartheid tension boiled over in Sussex, The Argus, 15th March 2020 (accessed August 2020). Also see: Jane, Goddard, New book by Burton author tells story of South African cricket’s ‘Tour de Farce’ in 1970, Derbyshre Telegraph Live, 27 February 2020 (accessed August 2020)

The Express stated they had ‘obtained a transcript of the proceedings’ of the AGM of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, a just-for-members event held in late October 1969, in London. With the Stop The Seventies Tour campaign (STST) about to start and the first blocking of a Springboks rugby match a week away, the proposed direct action was a hot topic at the AGM.

By ostensibly quoting internal discussions held at the meeting, the paper asserted that the AAM leadership ‘plainly entered into a conspiracy of silence about the direction future tactics should take’. The paper also alleged that the people who led the movement ‘gave a nod and a wink to its militants while at the same time saying: Don’t associate us publicly with this.’[2]Alain Cass and James Davis, Cricket Raids: the men who stayed silent, Daily Express, 22 January 1970

People present at the AGM at the time have rather different recollections of the discussions at the meeting. Christabel Gurney remembers that the officers of the AAM were concerned to protect the organisation from legal action and conspiracy charges (such as those that were subsequently brought in a private prosecution against Peter Hain). However, AAM members, including some – younger – members who were on the AAM’s Executive and National Committees, were free to join in whatever action they wanted to. Jonathan Rosenhead who also was with STST disagrees, saying: ‘We felt that AAM had become a bit fuddy-duddy in its rejection of new methods and youthful energy; maybe even concerned about possible reputational damage if they were seen to be our allies. Our view was that we were in fact doing AAM a favour – by shifting the centre of gravity of political discussion and action.’ [3]Email exchange with Christabel Gurney and Jonathan Rosenhead, 29 July 2020.

The Daily Express also published names of people present, and mentioned how two stewards at the door checked everyone’s credentials. For that reason, the three MPs assumed Special Branch had infiltrated the meeting and leaked to the press, taking their complaint to the Home Secretary. His staff took immediate action and summoned Ferguson Smith, the Head of Special Branch, to investigate the claims. The results are kept in a file ‘Complaint that police are passing information gained at meetings of the Anti-Apartheid Movement to journalists’, held at the National Archives.[4]See HO 325/117, Minister’s Case: Anti-Apartheid Movement; boycott of South African activities abroad, 1970, held at the National Archives.

Special Branch responded the very next day that there was no need to infiltrate the meeting. Ferguson wrote: ‘Both the [Daily Express] journalist… and we ourselves obtained a pretty full report on the proceedings from the same independent source’. The information, Special Branch explained, ‘was derived from a commercially-produced document copies of which are known to have been in existence since November 1969’:

The State Secretary subsequently had a meeting with the complaining MPs and related what Special Branch had told him. A note in the file says they ‘appeared satisfied as regards the article in the Daily Express’, accepting the explanation about the commercial report.

Special Branch cooperation with corporate intelligence agencies

No further questions were asked at the time about the police procuring commercial reports and cooperating with corporate intelligence providers. A shame, because – as it turns out – contemporary files retrieved from the National Archives are quite revealing.

In their report to the Home Secretary, Special Branch stated that it is was not difficult at all to get a copy of the commercial report. In December 1969, they had obtained one ‘directly from a well-tried source which is known to distribute such material commercially’. And in January 1970, they received another one ‘for enquiry’, after Sir John Lang (the Advisor on Sport at the Ministry of Housing and Local Government) had notified the Home Office.

The phrase a ‘well-tried source’ implies Special Branch obtained materials from this origin regularly. This is significant as it confirms that the Metropolitan Police worked with private intelligence agencies in the 1960s.

Special Branch and the Daily Express

What did the police do with the report obtained from the ‘well-tried source’ in November?

Special Branch wrote two reports on that year’s AGM. The first is dated 12 November 1969, and has the hallmarks of being written by someone not present. It contains phrases like ‘I have been informed’, it hardly has any information on who was there and otherwise sums up the motions filed during the day. Apparently an informant passed on the paperwork that circulated during the meeting.

The second report, from 15 December 1969, is much more detailed and includes the discussion about the plans of the Stop The Seventies Tour, and mentions the AAM’s executive committee’s reluctance to be associated with it publicly. Close inspection of the Special Branch report further shows the crucial bit of this discussion appeared in the Daily Express almost verbatim, in January 1970. This is just a small section to show the similarities (click to get to both documents to make a further comparison):

Also, both the paper and the report include the remark that ‘[f]or the first time in many years no report of the meeting was given in the Communist owned Morning Star’.

The similarities confirm that the December 1969 Special Branch report quoted from the same source as the Daily Express article did in January 1970. Which raises the question about the origin of the report, and how much Special Branch relied on it.

Copied Word for Word

While reluctant to reveal the source to the complaining MPs, the police were happy to give more detail about the information they – and the newspaper – procured:

This ten-page publication, incorrectly described in the article as a transcript, is in fact a report headed ‘Confidential’ and bearing the caption ‘Retrospect and Prospect, New Series No.2’, on the Annual General Meeting of the Anti-Apartheid Movement held at the National Liberal Club on 26th of October 1969, and it is presented as an eye-witness account illustrated with notes on the political affiliations and backgrounds of the personalities named.

Overly zealous perhaps, explaining how the Home Office forwarded them a copy as well, Special Branch included the attached department reference number: QPE 67 107/1/7. Now this file still exists and has been transferred to the National Archives as HO 325/116. It’s partly redacted, but the remaining content shows how the Home Office dealt with issues like this, and it reveals who circulated such reports.

The Home Office started this file when they first received a copy of the report from Sir John Lang as related above, and called it Retrospect and Prospect, AGM of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, October 1969 – after the title of the commercial report.[5]TNA: HO 325/116, Reports of AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, file opened in January 1970.

When, a year later, they received a similar report on the 1970 AGM, the HO changed the name of the file in to the more general ‘Reports of AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement’. Now it has become more than a one-off event.[6]TNA: HO 325/116, Reports of AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, file opened in January 1970.

One of the items the Home Office file holds, is a hard to read ten page report on the 1969 AGM of the AAM. It seems to be a carbon copy, typed up without any official captions, no police headings or reference to title of the commercial report, Retrospect and Prospect. However, the content turns out to be identical to the December Special Branch report quoted above, but for only two differences.

The carbon copy includes a numbered list of those present at the AGM, their role within the AAM, affiliations and other details known about them. Whenever someone is mentioned in the text, their name is followed by the corresponding number on the list between brackets. Additionally, added at the end is a section called ‘Observations’ with remarks on the amount of people present, the increasing involvement of young people in direct action, and the progress the AAM is making with the trade unions.

As mentioned before, the police described the report they obtained as ‘a ten-page publication […] presented as an eye-witness account illustrated with notes on the political affiliations and backgrounds of the personalities named’. This, and the similarities mentioned earlier, leads to the conclusion that this carbon print version is indeed a copy of the commercially-produced report. Probably it is the diligent work of a police officer who copied it to make sure no links to the ‘well-tried source’ would appear in the police files, before reworking it into an official Special Branch Report.

Following the paper trail, this detailed reconstruction of the sequence of affairs reveals that the 15 December Special Branch report on the AGM of the AAM was copied word for word from the commercially-produced report. To our knowledge this is the first time that such cooperation is documented: Special Branch procuring a commercial report, and presenting it as a product of their own with the intelligence gathered by themselves.

NOT THE ONLY TIME…

And it happened more often – or so it seems. A year later, the Home Office again received a report on the AAM AGM, this time forwarded by Lord Windlesham, Minister of State in their own department.

Subsequent correspondence shows that Senior civil servant Roy Sterlini wonders if he should send it to Box 500 [MI5] and/or Special Branch. His colleague McQueen, responsible for police at the department (F4 Division), remembers they had a similar issue the year before, and accordingly, they decide to again send it to Special Branch.[7]TNA: HO 325/116, Reports on the AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, file opened January 1970.

The next item in the Home Office file is the Special Branch report on the 1970 AAM AGM. With the rest of the file retained, whether the content is again copied from commercially-produced information is not confirmed – but highly likely.

Who did it?

There is a long tradition of cooperation between Special Branch (and MI5), private detectives and corporate intelligence consultancies. Employers, specifically the owners of large corporations, have increasingly created a market for this kind of information. From the late 1900s and early 2000s on employers have been afraid of the power of those organising at the workplace and destabalise the company with demands to improve work conditions, or strikes for a living wage. More recently, since the 1970s in the last century, groups and campaigns that hold big business to account for their growing negative impact on climate, human rights and working conditions have become a threat to the reputation of those companies, creating a similar market for intelligence to make a proper risk assessment. For more on the context, see Part 3, the last part of this short series.

The findings presented here in Part 1 are another piece in the puzzle of the largely unexplored field of the overlap and the connections between public and private, or rather corporate intelligence. The next step, Part 2 is finding out who did it, who produced the report on the AAM AGM and sent it to Special Branch .

References

| ↑1 | Samuel Brook, When apartheid tension boiled over in Sussex, The Argus, 15th March 2020 (accessed August 2020). Also see: Jane, Goddard, New book by Burton author tells story of South African cricket’s ‘Tour de Farce’ in 1970, Derbyshre Telegraph Live, 27 February 2020 (accessed August 2020) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alain Cass and James Davis, Cricket Raids: the men who stayed silent, Daily Express, 22 January 1970 |

| ↑3 | Email exchange with Christabel Gurney and Jonathan Rosenhead, 29 July 2020. |

| ↑4 | See HO 325/117, Minister’s Case: Anti-Apartheid Movement; boycott of South African activities abroad, 1970, held at the National Archives. |

| ↑5 | TNA: HO 325/116, Reports of AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, file opened in January 1970. |

| ↑6 | TNA: HO 325/116, Reports of AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, file opened in January 1970. |

| ↑7 | TNA: HO 325/116, Reports on the AGM’s of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, file opened January 1970. |